Australia’s energy transition

Big Brother government to confiscate tradies’ cars, using the proceeds to fund LGBTQI communes

Real men drive a Maybach Zeppelin

Belatedly Australia will soon join the rest of the “developed” world and have vehicle efficiency standards. You can get to the government’s consultation paper Cleaner, Cheaper to Run Cars: The Australian New Vehicle Efficiency Standard through a hierarchy of links, starting at the Department of Infrastructure, Transport etcwebsite.

As we make progress towards moving our electricity network to renewable energy, transport is on track to becoming our largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, and most of those emissions are from “cars”, a category that includes passenger vehicles and light commercial vehicles – utes and vans up to 4.5 tonnes or LCVs. This consultation paper is about cars so defined.

The paper provides a great amount of detail on vehicle emissions as justification for its initiative. Much of its international comparison uses the US as a benchmark. That country is renowned for its gas-guzzling vehicles, but in fact our fuel efficiency, for both passenger cars and LCVs, is worse than America’s. The government’s proposals are generally about bringing Australian standards roughly in line with America’s.[1]

The reader is left in no doubt that the government intends to legislate standards (that is, if the Greens and the Coalition don’t join in an unholy alliance to block it).

Its mechanism is a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, involving essentially a cap-and-trade system, allowing each importer a fair amount of latitude:

A NVES works by imposing a limit on CO2 (measured in grams per kilometre or CO2 g/km) each year across the fleet of vehicles that a supplier brings into the country. Each year the limit is reduced, so the standard becomes more stringent. Suppliers can still sell any vehicle they like, but will need to sell more clean cars to offset higher emission cars they sell. If suppliers sell more fuel-efficient cars than the target, they get credits. If they sell more polluting cars than the target, they need to buy credits from a different supplier or, eventually, pay a penalty.

Up for consultation is the extent of CO2 reduction to be achieved over the next five years, with separate targets for passenger cars (between 34 and 77 percent CO2 reduction) and LCVs (between 14 and 74 percent CO2 reduction), expressed as three options.

It comes across as a modest policy, written so as to avoid scaring the horses. The authors anticipate the likely less than rational response where they write:

We recognise that there are a range of different views in the community – especially given the cultural place that cars play in our society

Writing in The Conversation – Labor’s fuel-efficiency standards may settle the ute dispute – but there are still hazards on the road – John Quiggin explains the government’s intentions and the likely sources of opposition, even though the policy has been welcomed in many quarters, such as the NRMA. Importers Volkswagen and Hyundai support the move. Opposition seems to be confined to importers of US and Japanese monster LCVs.

Identity symbol?

The most recent Essential Report (February 13) finds that there is strong support for the standards: 55 percent of respondents agree that “more efficient cars will use less petrol and help drivers save on bills”, while only 15 percent disagree. It is notable, however, that Coalition voters show much less support for the standards than Labor and Green voters, suggesting that identity politics has made its way into the issue. It is also notable that women tend to be more in support of the standards than men. (A task to assign to bored kids in your car is to count the number of twin-cab monsters driven by men and by women.)

Peter Martin, writing in The Conversation – What would a vehicle efficiency standard for new cars cost - or save - Australian drivers? – summarizes the changes and points to US studies that found no general increase in car prices following legislation of fuel efficiency standards. He also quotes Dutton who claims that the price of a new Mazda CX30 would rise from $33 000 to $52 000. Dutton needs to learn marketing spin from his predecessor, Scott Morrison. Such idiotic exaggeration is akin to a dictator’s claim to have won 99 per cent of the vote: it lacks any credibility.

Quiggin also points out that the government in last year’s budget rolled back the Coalition’s instant asset write-off scheme, to take effect in July. That’s the scheme that allowed hairdressers to claim an instant tax deduction on a three-tonne twin cab to carry their clippers and shampoo. There may therefore be a rush of sales of monster twin cabs before the end of the financial year. For that reason our vehicle emissions may go up before they come down.

Before long the government will have to consider emission standards for trucks and buses. Any moves that reduce greenhouse gas pollution from diesel-powered vehicles will also reduce local particulate pollution. Writing in The Conversation Robin Smit of the University of Technology Sydney puts a convincing case for policies to develop an electric truck fleet: Why electric trucks are our best bet to cut road transport emissions. Anyone who has ever had to drive a heavy vehicle through stop-start traffic would surely welcome the acceleration EVs can deliver.

1. It’s hard to associate the USA with fuel-efficient vehicles, but their standards stem from the oil embargoes of the 1970s and 1980s, when the federal government and some states, most notably California, set standards to reduce fuel consumption. ↩

Electricity prices – we’re paying too much because of privatization

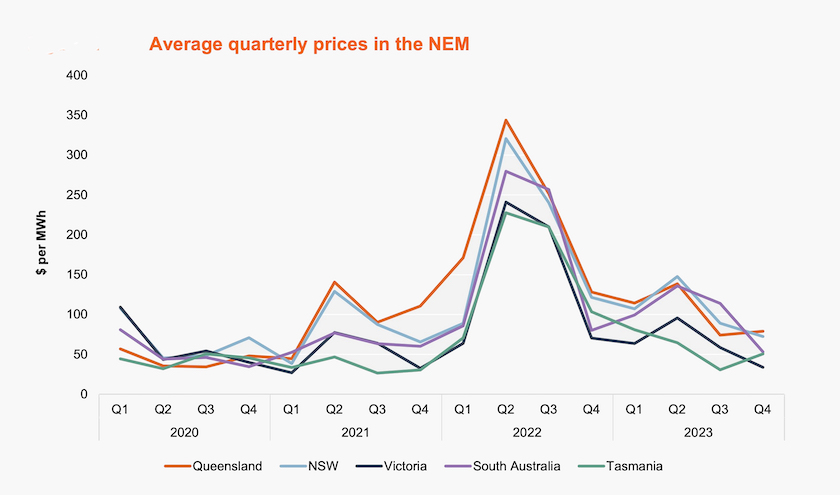

The graph below, copied from the Australian Energy Regulator’s January Report on wholesale markets, shows wholesale electricity prices, by state, in the National Electricity Market – essentially the eastern states including South Australia and Tasmania. For the peak in 2022 we can blame Putin.

The Grattan Institute’s Tony Wood explains what that means for power prices. He shows how wholesale prices relate to retail prices. There are the costs of transmission and distribution (“poles and wires”) to be covered, and almost at the end of the chain are “retailers” who are paid rather a lot for smoothing out the fluctuating wholesale prices which vary with time of day and with the performance of wind and solar supplies.

As Wood explains, wholesale prices are only a part of the price that appears at your meter. That is apparent from the graph: the Y axis shows prices in $ per MWh – not a familiar unit, but easily enough converted to familiar cents per kWh by dividing by 10. That means the wholesale price in the last quarter of last year was between around 4 cents (Victoria) and 8 cents (Queensland). That’s much less than the 25 – 35 cents we pay for electricity. Of course we have to pay for transmission and distribution, but those costs have risen significantly since these businesses were privatized and corporatized in the NEM “reforms”.

The NEM, designed by economists with little understanding of the engineering of electricity, was meant to separate the various elements of power supply – an idea based on economic dogma rather than on practicality. There hasn’t been much separation, however. The usual arrangement is that the big generating companies, AGL, Origin and Energy Australia, are also the retailers. They are sometimes called “gentailers”. They still operate like the old state-owned electricity companies, as vertically integrated companies with a great deal of market power, but they contract the transport of their product to the privatized and corporatized transmission and distribution companies. Because these transmission and distribution companies are monopolies their prices are regulated by the government, but on generous terms.

The NEM, in breaking up the old state-owned power companies, has laden us with an electricity system with high and unjustified profits, monopolistic gaming in price bidding, layers of transaction, legal and regulatory costs, and an opportunity for the fossil fuel industry to blame renewable energy for high prices.

The ABC’s Ian Verrender explains this in his post Electricity prices are crashing but don't expect cheaper bills anytime soon, where he writes:

The idea that the biggest power generators have been allowed to become the biggest retailers has been one of the greatest failures in Australian competition policy.

To a large extent, it was driven by the mania of state governments to privatise public assets. In their rush to maximise the short term gain, they were prepared to wave aside any considerations of longer term pain.

Wood explains that it will be July 1 before people see any reductions in retail prices. That should be politically convenient for the government, dealing with an electorate angry about power prices, and who have been lied to about the drivers of electricity prices.