Politics

How Dutton ran Home Affairs and would run the whole government if given the chance

For teachers seeking case studies of maladministration, the Department of Home Affairs is the gift that goes on giving. Right from the outset in 2017 there was something ridiculous about it, with that Monty Pythonesque name “Home Affairs”, conjuring an image of this wide brown land surrounded with a homely white picket fence. The name was grandiose: we had a Department of Foreign Affairs; by exception everything else fell to Home Affairs. It even had its own costumes, and militaristic names reminiscent of children’s games with toy soldiers. The task of immigration control became “Operation Sovereign Borders”.

So we should hardly be surprised to learn that it offered contracts to companies with probable links to arms and drug smuggling, corruption and bribery, that it was sloppy with contracting, was so assured of itself that it did not cooperate with other areas of government with law-enforcement and intelligence roles, and that it hired one of the Big Four consultancies to audit the wrong company.

Dennis Richardson’s Review of Integrity Concerns and Governance Arrangements for the Management of Regional Processing Administration by the Department of Home Affairs is cautiously written, but the details are all there.

Journalists have summarised its findings: the ABC’s Monte Bovill writes Home Affairs contracts awarded to companies with suspected links to drugs, firearms and bribery, and the Sydney Morning Herald’s journalists Michael Bachelard, Nick McKenzie and Angus Thompson writes Dutton ignored warnings as offshore processing show “rolls on”, says Labor. The report’s cover, pictured alongside, does a reasonably good job in conveying Richardson’s message: all that’s missing are the military costumes.

Richardson’s recommendations are mainly about governance, and the need for information-sharing across portfolios, particularly on matters where national security are involved. He also questions the whole raison d’etre for the department:

The formation of the portfolio of Home Affairs in 2017, which brought together a range of agencies, including the AFP and AUSTRAC, does not appear to have had any positive impact on working arrangements, at least in this area, again highlighting that coordination, cooperation and information sharing flows from policy, practice, mindset and culture, not from structure per se.

Fortunately for the government and the current head of the Department, this all happened on the Coalition’s watch, when Dutton was minister and Michael Pezzullo was Department head.

Dutton has the cover of a finding that seems to separate him from the department’s maladministration:

We did not see evidence of any ministerial involvement in the regional processing contract or procurement decisions, and the Secretary of Home Affairs said he never discussed such decisions with the Minister for Home Affairs. We did not come across any matter of deliberate wrong-doing or criminality.

Anyone familiar with the workings of the public service would realize that this doesn’t get the minister off the hook. It doesn’t do away with the principle of ministerial responsibility. The present Minister, Clare O’Neill explains this in a short (7 minute) ABC interview: “Don't ask, don't tell” culture fostered in Home Affairs Department. Of course she enjoys the Schadenfreude of a report that exposes Dutton’s hypocrisy – the tough cop on the beat who ignored warning signs of waste and corruption. Her political comments don’t negate the validity of her point about ministerial responsibility.

Ministers generally don’t issue written instructions to departments, and they don’t have to rely on specific directions: like staff in a luxury hotel, a public servant’s job is to anticipate what is required, without needing to be told. Ministers are heavily involved in appointing department heads, who, in turn, are heavily involved in sacking and appointing people in the next couple of layers of the hierarchy. These are sometimes people with partisan connections, and more often they are people who have a sharp sense of the ideology and values of the party in office and of their own minister. Whatever their background they shape the culture of the organization, and they take their design brief from the minister and his or her political party. It is beyond belief that the department would have made the same misjudgements had there been a different minister.

Exposed in these findings is a strong indication of how a Dutton-led government would function. We have been warned.

The right to ignore your phone and computer

According to the 13 February Essential poll, 59 percent of respondents support the so-called “right to disconnect”, while only 15 percent oppose it.

This probably understates support for the right, because the statement put to respondents implies a far stronger right than is actually in the legislation. The Essential statement reads:

A legal right for employees to disconnect after work has recently been proposed. This would legally prevent employers from contacting their employees, through any form of digital communication, outside of work hours. To what extent would you support or oppose the legal right for employees to disconnect?

In fact the law is far less prescriptive. It simply protects employees who choose to ignore unreasonable attempts by their bosses to contact them after hours. As the Sydney Morning Herald’s Angus Thompson writes in his bluffer’s guide to the new laws about getting contacted after hours, the key is what is “reasonable”. It’s about good manners, a concept alien to many on the right.

Minister Tony Burke covered this when he faced an aggressive and poorly-prepared Sarah Ferguson on the ABC’s 730 as he explained the legislation. It’s not a demand that an employer cannot make contact with workers. Where there’s give and take as in most work situations it will affect nothing. Rather it’s designed to address the situation where one can be punished for not being on call 24/7, when such availability is not a normal expectation of the job.

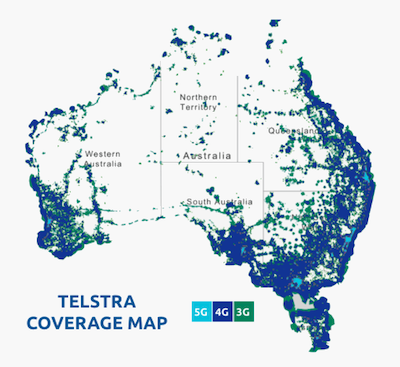

Do not stray from the blue shaded areas

Dutton’s promise to repeal this provision reveals his vision of the workplace. Rather than a place where people come together to create value and share the rewards of that effort, his model is of a feudal master-servant relationship, with an unquestionable and justified power imbalance. The master would be able to constrain his servants’ lives. They would not be allowed to go to national parks where cellphones do not reach, to join the military reserves or to take part in any activities that require disconnection. And surely Dutton, a former police officer, knows how people subject to intensely stressful situations have to be able to clock off entirely, for their own health – or perhaps he’s forgotten because police have had to beg him to keep the law in place.

Why, anyway, have Dutton and so-called “employers’” organizations made such a fuss of this minor aspect of the Closing Loopholes legislation – legislation that protects workers against wage theft and provides basic standards for gig workers? Is it to distract attention from these provisions, lest people realise that this legislation was brought on by the need to compensate for the Coalition’s deliberate and successful policy of suppressing workers’ incomes and rights?

The long-term drift to the left

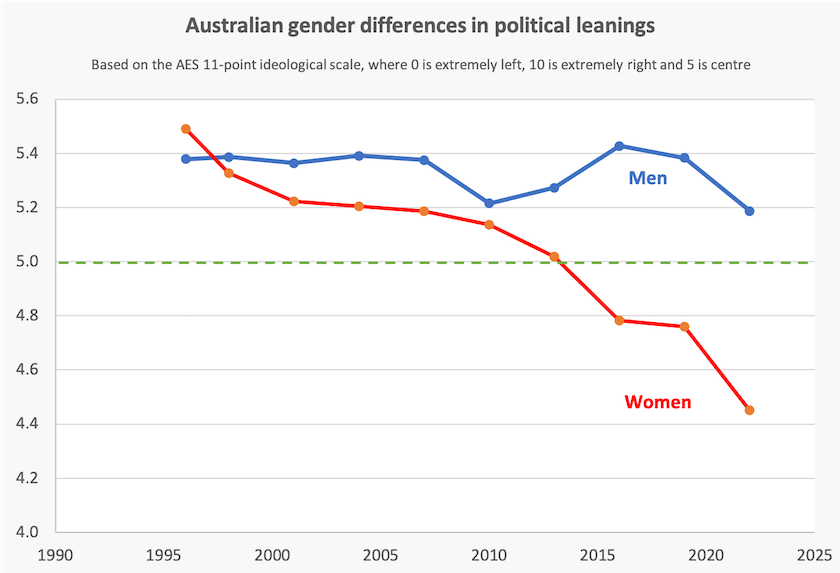

There are two trends in Australian politics. One is that the population as a whole is slowly drifting to the “left”. The other is that this movement is much more pronounced among women than men.

Intifar Chowdhury of Flinders University, drawing on Australian Election Study data, presents this finding in a Conversation contribution Australia’s young people are moving to the left – though young women are more progressive than men, reflecting a global trend.

The graph below is constructed from her data. It is hard to detect a trend among men – their movement seems to apply only to the last two elections, when the Coalition’s performance in office had been particularly odious. Also, internationally, there may even be a male drift to the hard right in some countries (Alternative für Deutschland, Hamas).

In Australia the split between the genders is well-established, having started around the turn of the century.