Health

Up to 9 million Australians can save money by dropping private health insurance

Many people struggling to make ends meet hold private health insurance. Do they really need it?

The answer is not simple: it depends on one’s age, general health, income and capacity to save, but there is ample evidence that many people could profitably drop PHI and make use of our public health system, or, if necessary, use private services financed from their own savings.

The ABC’s Mary Lloyd and Dinushi Dias have an informative consumer guide With the current cost of living, is private health insurance worth it?. As the name suggests it is better than those guides that are about the best PHI product for me; rather it asks people to consider whether PHI is worth having at all.

The answer is that for many people, particularly those of working age, and in reasonably good health, it may well be worth dropping it. If they are caught by the Medicare Levy Surcharges applying to people with incomes above $93 000 ($186 000 family), taking out the cheapest possible PHI product and never using it may be the best option.

Their article clearly explains the various subsidies and surcharges around PHI, the limits of PHI cover (you still have big co-payments and waiting times), and the government’s policies, described by health economist Professor Yuting Zhang at Melbourne University.

The government’s justification for encouraging people to take PHI is that it supposedly takes pressure off the public health system. That’s been the policy line of successive governments, Coalition and Labor, for about the last thirty years.

It is also wrong. Supporting PHI may encourage patients to shift to private providers, but it also encourages health professionals, including specialists, to move to private providers: where the money goes so too do the resources. The surgeon who once worked in a public hospital leaves the public hospital and moves to a private hospital to work, for much higher pay. (I have been one of many independent policy analysts pointing this out for many years: my most recent paper is an address to the 2018 Health Care Reform Summit The unbearable weirdness of health care.)

That’s why, as Zhang’s research shows, more people buying PHI makes little difference to the length of time people spend on public waiting lists. In allowing some to jump the queue for scarce resources everyone else has to wait a bit longer.

The incentives and subsidies, explained in detail in the Lloyd – Dias paper, are designed to force the young and healthy, mainly people of working age, to finance the health care needs of the older and frail – a task that can be performed at much lower cost and with greater equity by the tax system than by insurance firms.

That set of transfers is described in a 2005 paper Private Health Insurance: still muddling through, which shows, on average, that PHI works by having people aged under 60 subsidize those who are older. Policy settings haven’t changed much since 2005: thresholds for subsidies and incentives have simply been indexed upwards. Sixty is still roughly the age at which, on average, people start to get a positive benefit from PHI.[1]

Yet as revealed in APRA private health insurance data, of the 12 million Australians who hold PHI hospital cover, 9 million are under 60. That is, there are 9 million Australians, many of whom are finding it hard to make ends meet, who would do well to review their PHI cover, and assess whether they really need it. Some may judge that because of their particular health conditions they should hold on, some may decide to drop it, and some others, caught by the income surcharge may decide to take the lowest-cost PHI product and never to use it.

That’s about decisions for individuals. For the government there is a more basic question: why is it continuing to force people to support this high-cost and expensive financial intermediary in the health system, financed by a privatized tax, when a small rise in official taxes to fund Medicare would do a much better job at funding public and private hospitals? There was a time, up to the late 1980s, when Labor in government and in opposition understood and worked to establish Medicare as a single taxpayer-funded health insurer – the system in place in most other high-income countries. Our Labor government is now letting Medicare slide into a residual system for those without means – a path that leads to unfair and high-cost health care arrangements, as US experience demonstrates.

1. In fact it’s not clear that PHI, in spite of all the subsidies, is a good deal for people over 60. They are still served well in emergency situations by public hospitals, and if they really want to jump the queue for elective surgery, such as joint replacement, they can pay from their own savings. ↩

Giving Medicare teeth

Fifty years ago the Whitlam government took the nation to a double-dissolution election in order to implement Labor’s election promise to introduce universal taxation-funded health care. But strangely, dental care was left out of Medibank, as it was left out of Medicare ten years later.

The ABC’s Stephanie Dalzell explains this omission in a 2022 post: Why isn't dental included in Medicare?. Whitlam wanted to include dental care, “but negotiations with doctors consumed all the government's efforts and Gough Whitlam didn't want to bite off more than he could chew with dentists as well”.

A Senate Committee looking at access to dental care has produced its report A system in decay: a review into dental services in Australia. It makes 35 recommendations, 34 of which are directed at improving access to dental care through changes to existing programs, minor initiatives directed to particular needs, and measures to improve dental skills in the health workforce. Its 35th recommendation, which would eclipse most of the others, is to expand Medicare coverage to provide universal coverage.

It’s possible that the Greens, who chaired the committee (Senator Jordon Steele-John), may be the authors of this single recommendation. The other four Senators were from the Labor-Coalition coalition, and they probably favoured the 34 fiddles with existing provisions. In fact most submissions called for dentistry to be included in Medicare.

The Grattan Institute’s Peter Breadon and Anika Stobart have summarized the Committee’s work, and have re-asserted the economic case for including dental care in Medicare: Reform delay causes dental decay. To quote their conclusion:

Successive governments have skimped on dental care even as demand has risen. But those savings are a false economy that causes unnecessary disease and entrenches inequality. Today’s proposal for an overhaul should be the last – it’s time to fill this gap in the health system.

Road fatalities – have we picked all the easy hanging fruit?

Following rises in road fatalities in 2022 and 2023, road deaths are in the news. Deadliest six months on Australian roads since 2010 leaves industry demanding answers reads a Guardian headline in January. The Australian College of Surgeons have issued a news release about troubling statistics on road deaths.

The regular statistics published by the Commonwealth Office of Road Safety are concerning. They show that road deaths rose in both 2022 and 2023. Although these rises are not much higher than growth in population and in distance travelled, they are not in line with the targets in the 2021 National Road Safety Strategy, which includes a general target of reducing fatalities by 2030, and specific targets – zero deaths of children, zero deaths “on all national highways and on high-speed roads covering 80% of travel across the network” and zero deaths in city CBD areas. The graph of monthly road deaths on the Commonwealth’s BITRE website look particularly scary, suggesting that that what looks like an exponential rise is taking off. But that’s short term, and it includes the period in which people have been getting back on the road after the pandemic.

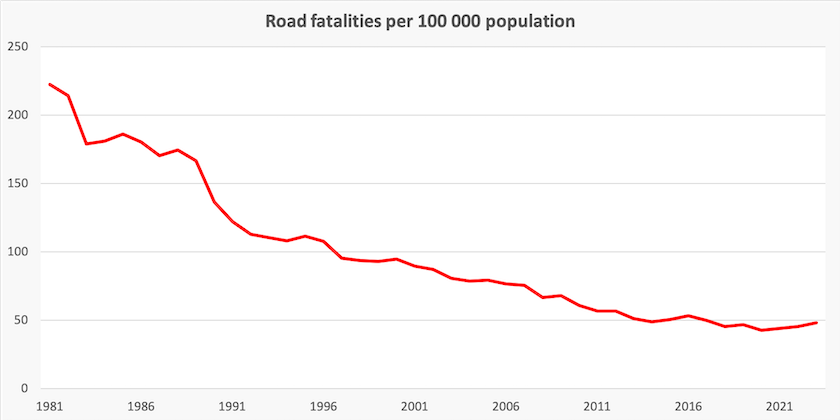

A glance at longer-term data on road fatalities, shown in the graph below, suggests that after many decades of lower road fatalities we have reached a level from which it may difficult to make further progress.

Seat belts, speed limits, random breath testing, safer vehicles, and safer roads have all yielded benefits. Is this as far as we can go?

International comparisons, including the BITRE’s International road safety comparisons, suggest we can go further. Several high-income countries have road fatality rates per 100 000 population and per million vehicles that are about half our rates. Some of these are small densely-populated countries, but Sweden, a country with long distances and a settlement pattern not unlike New South Wales, is one large country with less than half our fatality rates.

BITRE disaggregated data points to some areas needing specific attention in Australia. Almost 20 percent of deaths are of people not wearing seat belts for example. Because vehicle electronic systems can detect whether seats belts are fastened, it should be simple for the vehicle to transmit this information through RFID systems. Also around 11 percent of fatalities are in vehicles where the driver does not hold a valid licence. Both suggest some lack of effort in enforcement, and they also suggest that there is a core of people whose behaviour renders them accident-prone.

Milad Haghani, of the University of New South Wales, summarizes the BITRE data in his Conversationcontribution: Can we cut road deaths to zero by 2050? Current trends say no. What’s going wrong?.

One figure that stands out is that fatalities per 100 000 population are six times the national rate in areas classified as “very remote”, and the Northern Territory has a much higher death rate than the rest of Australia. Haghani notes that country and remote roads pose a high risk of death, relative to the population they serve.

Another figure that stands out from a separate BITRE publication on heavy vehicles is that there seems to be an upward trend in the number of deaths involving heavy rigid trucks, while there has been a small decline in deaths involving articulated trucks. Articulated trucks – semi-trailers and B-doubles – are likely to be operated by corporations, while rigid trucks are more likely to be operated by owner-drivers, or by businesses not specialized in transport.

The government response to our stalled progress is in a press release by the Assistant Minister for Infrastructure and Transport: Statement on the catastrophic number of road fatalities in 2023. (“Catastrophic” suggests an over-use of adjectives.) It includes attention to a number of measures, most of which involve small amounts of spending and most of which have been previously legislated or announced. It also includes a Commonwealth announcement that the New South Wales government will hold a road safety forum of “international and Australian road safety experts, advocates for motorists and road traffic victims, academics, as well as federal and state stakeholders”: Road safety forum to assemble top experts on road toll.

This modest response – recycling old announcements, making news out of tiny appropriations, and holding another conference – is strange, because the government has made some positive moves on road safety with the successful passage of The Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill. That bill has safety implications right along the transport scale – from food delivery workers on bicycles to owner-drivers of B-doubles. We might recall that in 2016 the Coalition government abolished the Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal, a body designed to make life safer for truckies (employees and owner-drivers) and all road users by establishing minimum pay and conditions. The National Road Freighters Association, who have worked with the Australian Road Transport Industrial Organisation and the TWU on shaping the bill, are reported to be very enthusiastic about the bill’s passage – “a fantastic outcome”, and an improvement on the old Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal: World-first legislation ensures minimum standards for truckies is the headline in the trade magazine Big Rigs.

The other government initiative that should improve road safety is its intention to introduce fuel efficiency standards for light vehicles (also covered in this roundup). It is possible that new standards will encourage people to hold on to older, less-safe vehicles, but that is a transitory problem. These standards may help remove some of the most dangerous vehicles from our roads. There is clear evidence that pedestrians and cyclists are at heightened risk when they there are heavy SUVs on the road. Also large SUVs and commercial vehicles, because they are heavy and have high centres of gravity, are more difficult to drive safely than cars and light utes.

These are appropriate and low-cost responses to a serious problem. But there is still a serious backlog in building safe main roads: the roads from Melbourne to Adelaide (the Dukes Highway), from Canberra to Yass (the Barton Highway) and from Brisbane north (the Bruce Highway) are murderously dangerous. They are heavily-trafficked, two-lane roads for most of their length, that should be of limited access standard. And we still have a non-metropolitan rail network little changed in layout from our last serious dedication to nation-building transport infrastructure in the 1880s. That’s because of a political obsession with debt, rather than a consideration of the state of our national infrastructure balance sheet.

The changing ways we mistreat our own bodies

We’re smoking less, but many young people are taking up vaping. There’s still a fair bit of binge drinking: about one in four men and one in seven women binge drink two or three times a month. Use of illicit drugs is still increasing – marijuana remains the drug of choice.

These trends are revealed in successive surveys by Melbourne University’s Household, Income and Labor Dynamics in Australia (HILDA), collated in a Conversation article by Roger Wilkins of the University of Melbourne: HILDA survey at a glance: 7 charts reveal we’re smoking less, taking more drugs and still binge drinking.