Education

How are schools performing?

“School refusal is on the rise, teenagers are dropping out at record rates and public schools are continuing to lose out on funding”.

So reads the article by the Guardian’s education reporter Caitlin Cassidy, School dropouts and the public v private funding gap: five takeaways from the Productivity Commission’s education report.

The report to which she is referring is the School Education component of the Commission’s annual report on government services. You can follow the Commission’s findings from a series of drop-down menus of “indicator results”, or from Cassidy’s consolidated summary in her article.

On funding it’s hard to reconcile Cassidy’s figures precisely with those in the report, but it’s clear that private schools have had a greater real growth in public funding than public schools. A little arithmetic applied to the Commission’s figures confirms that between 2012-13 and 2021-22, real recurrent funding per student for government schools rose by 23 percent, while it rose by 37 percent for non-government schools. Writing in the Saturday Paper (paywalled) – The federal government needs to get serious about properly funding public schools – Jane Caro reminds us that successive Commonwealth governments have quietly ignored the Gonski recommendations, that elite private schools are already extraordinarily well-funded ($42 000 a year in one Sydney school), and that Australian schools have some of the highest levels of social segregation among all “developed” countries.

The Commission’s data on attendance, retention, attainment and outcomes all point in the wrong direction.

Between 2015 and 2023 school attendance rates in Years 7-10 fell from 91 percent to 86 percent. The fall was somewhat steeper in government schools.

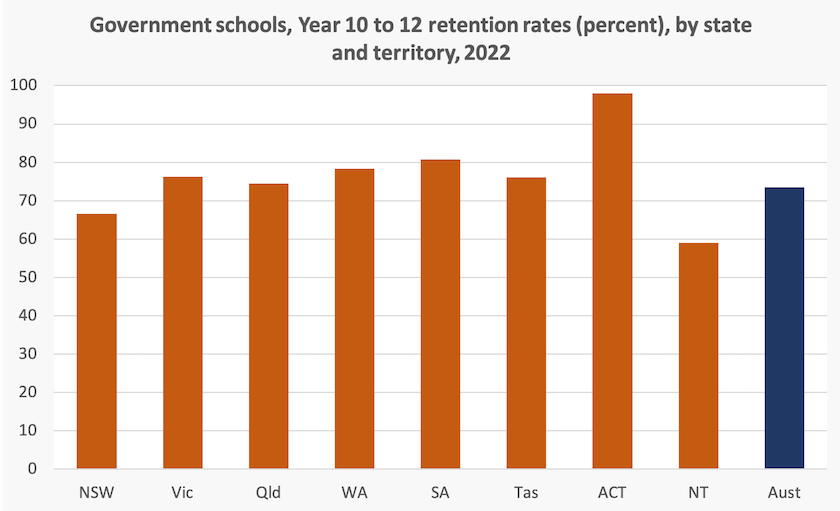

Between 2013 and 2022 the percentage of Year 10 students continuing to Year 12 fell from 81 percent to 79 percent. Government schools have particularly low retention rates – 74 percent in 2022. Also there are significant state-by-state differences, as shown in the graph below. Note the low retention rate in New South Wales:

Anther regional dimension revealed in the Commission’s data is that school attendance drops off as a student’s distance from a capital city increases. This is evident in all states, and most notably in New South Wales.

It would be informative if the Commission in its future reports could disaggregate attendance and retention data by gender, because there are many anecdotes about girls being more engaged with schooling than boys.

The Commission reports on Australian schools’ scores on PISA and other international metrics. Between 2009 and 2022 our PISA scores on reading, math and science have been declining.

In relation to reading there has been a raging battle over the way children are taught to read – the “whole language approach” versus the “phonics” approach. The only thing that has united the most strident advocates is a belief that one approach should serve all children. The Grattan Institute has reported on the results of our reliance on the former approach noting that “In the typical Australian school classroom of 24 students, eight can’t read well”.

In their report The Reading Guarantee: How to give every child the best chance of success, Jordana Hunter, Anika Stobart and Amy Haywood urge what they call a “structured literacy” approach which combines elements of both whole of language and phonics, with an emphasis on phonics in early years.

Writing in The Conversation, Zid Niel Mancenido of Harvard University draws attention to 2022 data revealing that Australia’s classrooms rank among the OECD’s most disorderly, and to a recently-completed Senate committee report (The issue of increasing disruption in Australian school classrooms) on teachers’ difficulties in dealing with behavioural problems. Mancenido’s article -- A new Senate report sounds alarm bells on student behaviour – summarises the Committee’s report, which is largely in the context of Australia’s declining performance on PISA results.

The problems identified in these reports result from many years of poor public policy, generally on the Coalition’s watch. We can only speculate on the reasons the Coalition allowed our public schools to run down. It may stem from their belief in “small government”, that sees public funding of health and education not as a shared social contract, but as a form of distributive welfare, providing a basic service for the poor and disadvantaged. It may be that they believe Australia’s economic future lies in low-skill-low-pay jobs, requiring little education for the masses: John Howard, whose ideology has shaped the Liberal Party, bemoaned the disappearance of “dead-end” jobs in the Australian economy. Or, at worst, their policy may not have had the backing of any public ideas, but was simply about supporting their class interests.

John Hewson on universities

Over the last few years we have seen tradies doing very well financially, while university graduates, often carrying the liability of high student debt, have found it increasingly hard to find well-paid employment in their fields.

University of New South Wales

As John Hewson writes in his regular Saturday Paper contribution (paywalled), this has contributed to a flattening in university enrolments and to the dropout rate of university students reaching an all-time high: In the era of the tradie, university education is being undervalued.

He fears that we have lost sight of the real purpose of university education:

It has been an increasing weakness that a university degree is mostly looked at as an alternative in the spectrum of vocational training. It is much more. University training provides a framework for disciplined thinking – developing a capacity to think through an issue, to initiate, marshal and research evidence to move towards and even challenge the frontiers of the fields of knowledge.

That is not to devalue the skills and competence of people who have gone through the tough discipline of mastering a trade. The well-educated person has mastered both university and trades skills, and has respect for both paths to knowledge.