Public ideas

Re-imagining Australia as a conquered country

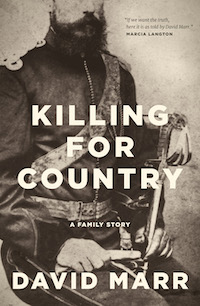

When David Marr discovered one of his ancestors had been in the native police, he set out to write about their part in killing indigenous people. The project started as what may be called a family expose. But as he worked on the project he came to understand that it was not just about one man and his involvement in terrible deeds. He had been part of a systematic and well-organized program of dispossession and murder.

Marr came to see Australia not just as a country with some disgraceful incidents in its history. Rather he came to realize that “we’re a conquered country”. That conquest was uniquely brutal and devastating, the cruellest in the whole history of the British Empire. We therefore have an obligation to the conquered.

If you can spare 40 minutes, you can hear David Marr discuss his re-imagining Australia with Larissa Behrendt on the ABC. Speaking Out program. Marr’s book about his journey into our history is Killing for country: a family story. It’s far more than a family story: it’s a story of our country.

The democratic retreat analysed

Why have authoritarian populists attracted so much support in countries that have reasonably free elections?

Martyn Goddard deals with this question in his Policy Post Populism and the fight for democracy. He provides plenty of data confirming that worldwide, democracy is in retreat. In just 7 years, from 2015 to 2022, 27 countries became less democratic as indicated by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. In some countries still classified as democracies many people believe that democracy is not working: 41 percent of Australians are dissatisfied at the way democracy is working here. Faith in democracy, he notes, relates closely to people’s trust in government, which has also fallen.

He describes the workings of populism. It’s about mustering support from the “real people”, the “silent majority” – the people upon whom the “elites” supposedly look down. He describes the anxieties and fears exploited by populists – inequality, insecurity, immigration, lack of housing. And as case studies he compares two campaigns, one successful (same-sex marriage) and one unsuccessful (the Voice), both of which the populist right had set in the frame of real people vs elites.

What can we learn from Marcus Aurelius – not much perhaps?

Marcus Aurelius ruled the Roman Empire at the time it was confronting a raft of challenges – “major wars on the Euphrates and the Danube, a massive plague that took an estimated five to 10 million lives (in an imperial population of 80 to 100 million), and inflation, which led him to debase the coinage in order to pay the Empire’s growing bills.”

So writes Paul Monk in the Rationalist Society magazine Rationale: Marcus Aurelius and stoic politics.

Although Marcus Aurelius’ cautious and unadventurous style is valorised by historians as a style to emulate, Monk argues that it was not suited to its time, and should not be a style for our time, as governments face similar challenges. Just as Rome needed vision and innovation to arrest its decline, so do we.