Education

Two reports, one on universities, the other on schools, have the same themes. One theme is about the skills gap we must close if our economy is to thrive in a tough international environment. The other is about closing an education gap that’s threatening our social cohesion. Action on both will require significant increases in public expenditure, and therefore collection of taxation.

Universities – towards an educated and competitive nation

Australian National University

The most striking aspect of the Australian Universities Accord Report is its call to lift “the tertiary attainment rate of all working age people (with at least one Certificate III qualification or higher) from 60% currently to at least 80% by 2050.” That’s about bringing up our standards: to raise them up to ongoing requirements, 90 percent of 25 to 34-year olds will require a tertiary education by 2050.

We may be conditioned to think of “tertiary education” only in terms of bachelor or higher university degrees, but the report’s authors use the OECD’s more inclusive idea of “diploma or above degrees (diploma, advanced diploma, bachelor, graduate certificate). It also assumes that the distinction between universities and other institutions is lessened, where it states: “To make qualification attainment faster and easier, Australia should ensure students can more seamlessly navigate between VET and higher education.”

Whatever way we look at these numbers, its vision is clear: completed tertiary education should be the normal expectation, just as once it was Year 10 and later Year 12. This is not only about our skills gaps, where we have been falling behind other countries. It is also about social cohesion, particularly protection against the division when public policy becomes a struggle between the schooled and unschooled.

In this regard the report has a strong emphasis on equity, particularly in overcoming the financial barriers faced by young people from low SES background and regions remote from centres of learning. It’s about preventing human capabilities from being wasted, and about closing social divisions.

Its 47 recommendations cover a large number of issues in tertiary education. Perhaps the most important is the need for research to be funded specifically, because in coping with underfunding over many years, universities have been relying on cross-subsidizing postgraduate education and research from a surplus generated in large undergraduate courses, financed by native and overseas students.

Although it acknowledges the burden of high student debt, it is vague about ways to lighten the load. It calls for “Student contributions that are fairer and better reflect the lifetime benefits that students will gain from studying and HELP loans with fairer and simpler indexation and repayment arrangements.”

But if everybody, or nearly everybody, has a tertiary education, there won’t be many specific personal lifetime education benefits, as there once were when only a minority of Australians had university degrees. The report’s authors duck an important issue: how we set the boundary between taxpayer-funded universal education and personally-funded education. Why should that stay at Year 12? If, as the authors convincingly argue, the benefits of tertiary education are economy-wide, why does it not put the case for funding to be shared through taxation, rather than through fiddling with HELP?

If this and other reports on university funding aren’t to degenerate into a TAFE vs University, or an “elites” vs “ordinary Australians” battle, the public needs much more understanding of the benefits of technical andliberal education. The first is about the specific skills we need today, the second is about critical thinking and problem-solving – the agility we need to live in a changing world. We need both.

The recommendations are unsurprisingly generating a great deal of commentary from the university community. I have picked just four from The Conversation, covering the report’s main aspects.

Judith Ireland, education editor of The Conversation, explains the report’s origin and summarises its recommendations: Universities Accord final report: what is it, and what does it recommend?

Peter Hurley and Melinda Hildebrandt of Victoria University (not to be confused with the old, established University of Melbourne) write about the report’s emphasis on “needs based funding”, which would involve some re-allocation from old, comparatively well- endowed universities to other institutions: “Gonski-style” funding is on the table for higher education. This will see some unis gain more than others. On ABC Breakfast Patricia Karvelas interviews University of Sydney Vice Chancellor Mark Scott about the report – “A bold direction”: What is the Universities Accord, and is it achievable? Understandably the VC of Australia’s oldest university is less than enthusiastic about the report’s funding re-allocation suggestions. The problem, he explains, is “chronic underfunding” of all universities.

Gwilym Croucher of the University of Melbourne draws attention to the way students presently pay for tertiary education, including the workings of the HELP scheme, and comments on ways the report proposes to lighten the load, including the important recommendation for helping students through compulsory professional placements (including in teaching and nursing) . As the title hints -- Many students could pay less for their higher education … eventually – the report’s recommendations for easing the financial burden on students are modest.

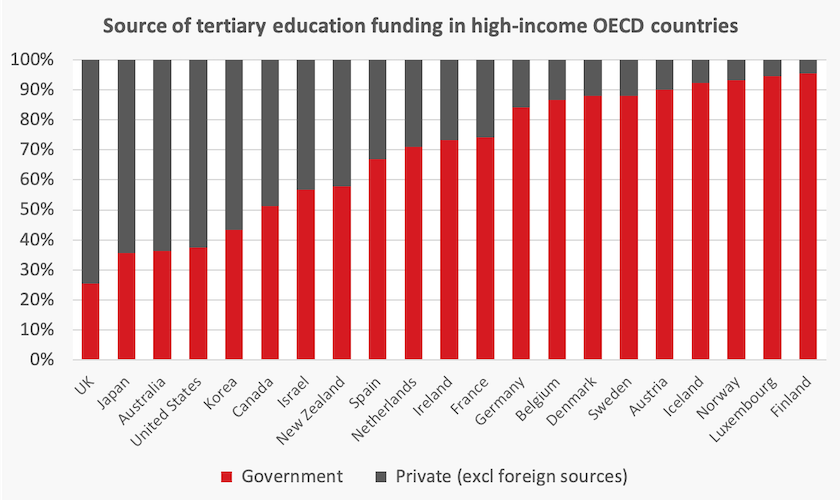

Croucher’s contribution has an informative graph of spending on tertiary education by government and non-government sources. For some reason he leaves out the USA, and shows total spending, which is clearly influenced by population. Below is a graph of percentage spending by source, for high-income OECD countries, drawing on the same data set that Crowther uses. Australia, with its high dependence on private sources, is clearly in a minority.

Another Conversation comment on the burden faced by students is by Sally Patfield of the University of Newcastle: The final report mentions “equity” 200 times, but can it boost access for underrepresented groups? It’s an important contribution, because while she notes positively that, if implemented, the report’s recommendations will develop a student population that is more representative of Australia, she questions the report’s rationale about “aspiration”. What’s holding poorer and more remote people back – financial barriers or a lack of aspiration? The report asserts, for example, that “increasing equity in tertiary education requires raising aspiration levels among currently under-represented groups through outreach programs to develop familiarity with higher education”. She believes the aspiration is already there.

Most probably both aspiration and financial barriers are at play. There is no doubt that many immigrant groups aspire to tertiary education. But it is also possible that among native Australians there are pockets of redneck culture, particularly in the country, where a lack of schooling can be seen as a badge of honour. A half-century ago the Menzies government oversaw a huge expansion in tertiary education, but the Howard, Abbott and Morrison governments have all tended to denigrate tertiary education while valorising ignorance and anti-intellectualism.

Schools – don’t forget the hardware

A classroom, even if demountable, is a good help for learning

Schools need classrooms, but that’s only a start. Schools need libraries, laboratories and some sport facilities. They probably need a school hall, but that can be anything from a shed that doubles as a gym through to a purpose-built theatre with tiered seating. Should a swimming pool be part of standard school infrastructure? How about rowing – boats and a shed? An indoor equestrian centre perhaps?

The Australian Education Union, in a report Ending the capital funding divide in Australia’s schools, brings to our attention the infrastructure deficits in public schools. It finds:

Despite the benefits of modern and well‐designed learning spaces and continual population growth, over the last decade infrastructure in Australia’s public schools has been steadily deteriorating, and Australia’s public school building stock has a high prevalence of aging buildings with issues ranging from leaking roofs to unstable structures and inadequate facilities like science labs, libraries, and sports areas – all of which are essential for a holistic education.

It contrasts this situation with more generously-funded capital infrastructure in private schools, some of which is funded by Commonwealth capital grants to non-government schools, some of which is funded by parents and alumni, helped by the tax deductibility of capital contributions, and some of which is from diversion of excess recurrent funding to capital works.

The report’s most striking example compares the capital expenditure by just 5 private schools, which was more than the capital expenditure by 3372 public schools:

In 2021, five individual private schools spent more on capital works ($175.6 million) than more than 50% of public schools in Australia combined ($175.4 million). These 3,372 public schools with the lowest capital expenditure educate 842,120 students. The five individual private schools educate a total of 10,294 students and outspend the bottom 50% of public schools by 82 times on a per student basis.

It draws attention to the contrast between Barker College’s plans to spend $150 million on a performing arts and exam centre (it has just finished spending $40 million on an indoor sports complex) and the 5093 demountable classrooms in New South Wales public schools.

The Union’s report comes after a Productivity Commission draft report on philanthropy – Future foundations for giving – presented in November last year. It was about all philanthropic donations, and the justification or otherwise for tax deductibility. Notably it found that school building funds are almost the largest category of entities eligible for donor tax deductions, second only to public benevolent institutions. On schools it wrote:

There are also some charitable activities where the reasons for DGR [deductible gift recipient] status have lessened over time. School building funds – which are widely, but not exclusively, used by non-government schools – are a case in point. School building funds were given DGR status in 1954 when government support for non-government schools was very limited. Since then, government support for non-government schools has expanded considerably. Providing indirect government support through school building funds means government funding is not prioritised according to a systemic assessment of the infrastructure needs of different schools.

On tax deductibility it found there was “no explicit policy rationale justifying why some charitable activities are within scope, but others are not”.

Mostly, when we donate to a charity, there is no private benefit beyond a warm and fuzzy feeling. Donations to school building funds are close to private benefits, as the Commission pointed out:

The Commission’s view is that converting a tax-deductible donation into a private benefit is, in principle, a substantial risk for primary and secondary education, religious education, and other forms of informal education, including school building funds. The potential for a donor to be able to convert a tax-deductible donation into a private benefit is especially apparent for primary and secondary education, particularly where students are charged fees.

In fact in a 2004 analysis of tax deductibility of school building funds the Australia Institute found that for many private schools, a donation to the building fund was either “assumed” as part of the deal, or even explicit in some cases, clearly in violation of the ATO rule that they must not provide a material benefit for the donor, such as a reduction in school fees or receipt of a scholarship.

For now the government is not addressing the question of tax-deductibility of school building funds: it will wait for the Productivity Commission to produce its final report later this year. The Financial Review’s Tom McIlroy has alarmed the private school lobby with the headline Private schools could lose building fund tax cuts, evoking claims from schools and parents’ groups that the withdrawal of benefits would be detrimental to children’s education.

Maybe they’re right. Maybe a specialized theatre and a swimming pool are important for children’s education. But if that is so, it reinforces the case for all schools to be brought up to standard. When it comes to the extravagant end of the spectrum, it’s probable that even if they do yield educational benefits the gains are minor, and the money would be better spent on other school enhancements.

The real policy challenge is to use public funds to bring all schools up to a high standard – the full Gonski. That certainly requires some re-allocation, as the Union points out, and it also requires a significant lift in funding.