Politics

Dutton’s mission to Make Australia Afraid Again

In his Quarterly Essay Bad Cop: Peter Dutton’s strongman politics Lech Blaine gives us a fine-grained picture of one who is out to “Make Australia Afraid Again”.

For most politicians the scare campaign is a calculated tactic, adopted on the advice of experienced party elders or campaign consultants, but for Dutton it comes easily, because of his life experience.

Blaine explains how Dutton’s Weltanschauung was conditioned by nine years in the Queensland police force, including a posting in Townsville where he was to confront toughened, drug-addicted, violent lawbreakers, whom we have good reason to fear.

We may believe that such conditioning would shape him into a “law’n’order” politician, but that’s too simple, because, as Blaine explains, Dutton has contempt for the rule of law. As is the experience of many cops, he has endured the frustration of seeing the courts set free people who, to the police, are obviously so evil and dangerous that they should be locked away for life. To Dutton, defence lawyers, magistrates and judges are part of the woke establishment. Whether it’s the elected government, or the High Court overturning incarceration of offenders who have served their terms, it’s all the same.

Blaine’s essay is a biography of Dutton, descriptive rather than judgemental. It would be hard, however, to read about Dutton’s administrative decisions as immigration minister that favoured “whites”, his alliances with Pauline Hanson, and his handling of the Voice campaign, without wondering why the Liberal Party has chosen Dutton to stand for the highest office in one of the world’s most multicultural nations.

In spite of extensive research, Blaine has been unable to tell us much about Dutton’s ideology, leaving us with little idea of what sort of policies he would pursue if in office. On economics the closest he can get to any sense of policy is covered in one sentence:

Economics is not his emotional priority, beyond a tribal allegiance to tax loopholes for the rich; penalties for the poor; and hostility to trade unions.

Why, then, does he want to become Prime Minister? Is he one of those politicians who the Harvard psychologist David McClelland found to be seeking high office as an end in itself, to fill a personal need, perhaps as a means of righting some wrong? In her Conversation review of Blaine’s essay Judith Brett explores this possibility, where she writes:

Blaine gives a compelling account of Dutton the strong man, but he also claims that if you watch him for a long time, you see a man who is small and scared. The pioneering political psychologist Harold Lasswell says politicians like Dutton, preoccupied with the management of aggression and with provoking reaction, are driven by low self-esteem and a compulsive need for deference.

That could also be a description of the Liberal Party, whose raison d’etre in opposition is to right the obvious wrong of the people having elected Labor to govern, rather than to pursue any vision of public policy of their own.

In Dutton maybe they have found the ideal candidate, because he will overcome the party’s insecurity and take up the fight, even if the evil intentions of the enemy have to be invented. He’s the tough cop on the block who can protect us from the imagined horrors of “Arabs arriving by the carload in white beachside suburbs and dark-skinned rapists on the loose”. Blair writes:

Dutton became a man frozen within a period of fear. Trauma made him soft. In lieu of psychological attention, control made him feel solid and safe again. Always displaying simplicity and strength. Because he feels so complicated and weak.

Some readers may be disappointed that while Blaine has exposed many instances of Dutton’s acts of political bastardry, he has not countered his scare campaigns and misinformation. But as Ed Cooper points out in his book Facts and other lies: welcome to the disinformation age, such effort is generally futile. It does nothing to convert those who have closed their minds, helps publicize the liar’s message, and overstates the liar’s power. It is better to expose the scaremonger’s tactics and fragilities, and these are well exposed in Blaine’s essay.

He leaves it to the reader to assess whether Dutton has the moral and intellectual qualities that would suit him to hold high office in a democracy. Only in the last short paragraph of his essay does Blaine suggest where his judgment lies.

Don’t believe the law’n’oeder scaremongers: Australia is getting safer

Media reports suggest that crime rates were a significant issue in causing large swings against the state government in two recent by-elections in the western fringes of Brisbane. Dutton exploits people’s fear of crime in his political campaigns, regardless of what is revealed in the evidence.

So it’s worth looking at the evidence of people’s experience of crime. In the last few days the ABS has published updated data on crime victimization over the last 14 years.[1] The graphs below show victimization rates for crimes covered by the ABS time series,[2] first for what they classify as “personal” crimes:

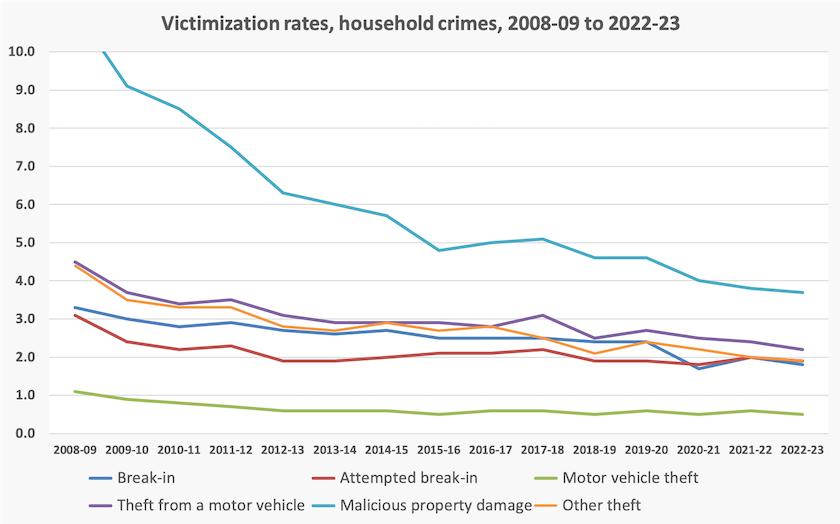

Then for what the ABC classifies as “household” crimes:

In all 11 categories, other than sexual assault, the trend is downwards. Data on sexual assault is influenced by a rise in the willingness of victims to report cases, which has almost certainly increased in recent years. Examination of separate ABS data on personal safety, reveals that in the vast majority (around 90 percent) of cases of violence against women, including sexual assault, the perpetrator is known to the victim. Nothing in ABS data supports suggestions that women face any increased threat from unknown sexual predators at large in the streets.

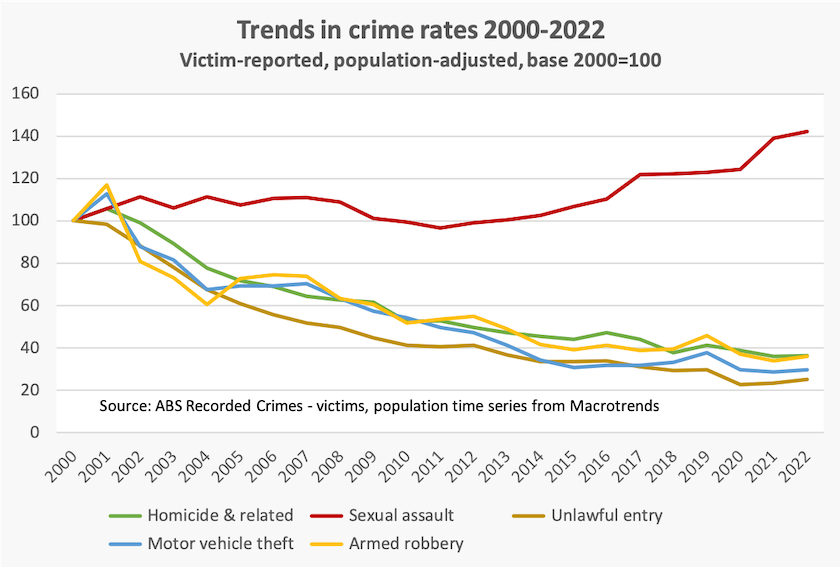

ABS surveyed victimization data goes back only to 2008. ABS data on recorded crime (recorded by law-enforcement authorities, rather than victims) shows a sharp fall crime in crime so far this century, again with the exception of sexual assault. The graph below shows national trends.

Just as no opposition party is justified in raising anxiety about crime, no government should claim bragging rights for the trends. In part they have to do with demographics as the proportion of young males in our population diminishes. In part they have to do with the declining rewards from crimes such as robbery: stuff that was worth stealing 20 years ago is now practically worthless on the fence market. And in part it’s because cars and phones have become harder to steal.

So long as there is any level of crime, however, there will be plenty of stories for the media. Just one or two cases of horrific rapes or murders suffice to elevate people’s fear of stranger danger. Also there are regions where there is a concentration of crime: the media has had a ready feed of stories of kids stealing and smashing cars in Alice Springs, Mount Isa and Townsville. Poorer people whose cars are old and easily-stolen are disproportionately the victims of car theft.

And as Rick Brown of the Australian Institute of Criminology reminds us in a recent report to Canberra Timesjournalists, while the rates of armed and unarmed robbery involving physical interactions have tumbled in the last twenty years, cybercrime is on the rise. The nature of robbery is changing: You may not carry cash, but here's why you're a bigger target for theft. (Paywalled) The ABS has published data on personal fraud, showing that while there is a downward trend in scam victimization, card fraud is on the way up.

The ABS and the Institute of Criminology keep us well informed about the visible costs of crime, even if politicians choose to ignore it. It’s much harder to estimate the cost of the fear of stranger danger, a fear elevated by opportunistic journalists and politicians.

In fact the fear of assault has a positive feedback mechanism, because it results in people becoming reluctant to use public parks and public transport, resulting in these places becoming more attractive to criminals. Moreover there are direct costs to public health when people are housebound by fear, and costs to society more generally when people do not mingle with one another in public spaces. The costs of these false perceptions of crime, generated by irresponsible politicians and journalists, could well be higher than the cost of crime itself.

1. The series on victimization starts in 2008-09. The ABS definition: “Victimisation rate refers to the total number of persons aged 15 years and over who experienced a crime type in the last 12 months, expressed as a percentage of all persons aged 15 years and over (18 years and over for sexual assault)”. ↩

2. These are as selected by the ABS, covering crimes for which national data can be consolidated from state data. ↩