Kids’ politics

Banning kids from social media – a moral panic or sound public health?

New South Wales and South Australian premiers Chris Minns and Peter Malinauskas have asked the Commonwealth to set national restrictions on children’s use of social media. This follows their impassioned calls for action at a social media summit, organized as a cooperative venture by their two governments. One of the most influential speakers at the summit was Jonathan Haidt, author of the 2018 book The coddling of the American Mind, and this year his book The anxious generation. Among the participants was ASIO director-general, Mike Burgess, concerned about radicalization and quite a few young people, according to the ABC’s Sophie Holder: A summit brought together experts, government and teenagers to talk about social media's impacts and a proposed ban. Here's what happened.

Communications Minister Michelle Rowland has committed the government to legislating restrictions by the end of the year, setting a minimum age and other conditions, yet to be determined. The onus for compliance will be on platforms, with no penalties for parents or children breaking restrictions. There will be exemption for “low risk” platforms, but Lisa Given of RMIT University, writing in The Conversation warns that there are difficulties in specifying what is “low risk”. Peter Malinauskas, in a short interview on Radio National addresses some of the technical issues in identifying account holders’ age and giving parents control over children’s use. Although some children will find workarounds, effective regulation is possible he believes.

The idea for some form of restriction has attracted little criticism – what can be wrong with protecting kids? But is this a moral panic in the age-old tradition of parents fearing that their kids will enjoy something they didn’t enjoy when they were children? The issue is far from clear cut. Des Griffin, one of our readers, has brought our attention to an academic dispute between Jonathan Haidt and other social researchers, who claim Haidt has confused correlation with causation. If you want to go into the details of this dispute you can read Eric Levitz’s criticism of Haidt’s methodology, What the evidence really says about social media’s impact on teens’ mental health, and Haidt’s defence Social media, not the economy, is harming teen mental health.

There certainly has been a rise in mental illness and anxiety among children, particularly teenagers. This was noted in the March 30 roundup, which has a link to the World Happiness Report showing growing discontent and unhappiness among young people in recent years. At the same time there has been a big uptake of social media by young people. Depending on the time periods chosen for research, it is possible to find strong correlations between rises in mental illness and social media use, but as the old warning goes, correlation does not establish causation. Other stuff has been going on – Covid, housing stress, tighter jobs prospects for young people. And it is possible that social media is a means of relieving stress. Establishing causation is a difficult problem in social research.

We may be looking at something that started happening long before social media appeared. Des reminds us of a 2011 article by Peter Gray in the American Journal of Play: The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents, in which he concludes:

Over the past half century, in the United States and other developed nations, children’s free play with other children has declined sharply. Over the same period, anxiety, depression, suicide, feelings of helplessness, and narcissism have increased sharply in children, adolescents, and young adults.

Gray goes on to point out that play functions as the means that children develop social competencies that will serve them in adult life. In 2011 Myspace and Facebook were in their infancy. On Page 449 of Gray’s paper is a table showing an extraordinary rise in indicators of mental illness and stress among teenagers between 1948 and 1989. In 1989 the nearest things to social media were bulletin boards.

At the end of Levitz’s article in which he criticizes Haidt’s research, he breaks from academic style and writes:

But it still seems doubtful to me that kids are benefiting from spending less time hanging out with close friends in person and more time performing their selves on social media platforms in an often invidious competition for approval and attention.

In a Radio National ABC Breakfast interview on the general issue of protecting children from harmful content Mark Weinstein, author of Restoring our sanity online: a revolutionary social development, reminds us that it took 200 years to adjust to the new technology of printing; we are still in the early stage of dealing with social media. The even broader issue is the way digital media facilitates proliferation of misinformation, hate speech, scams, invasion of privacy and other social harm. That’s the subject of a post by ABC’s social media journalist Esther Linder How getting big tech platforms to care for their users could mean a better online experience for everyone. If the platforms, with all their resources, cannot exercise a duty of care, why should governments not shut them down?

Youth crime in perspective

We all know that youth crime is on the rise, don’t we? We have seen those news clips from Alice Springs, Mount Isa and Townsville, showing children stealing cars and wrecking them, trashing small businesses, and making city streets into combat zones.

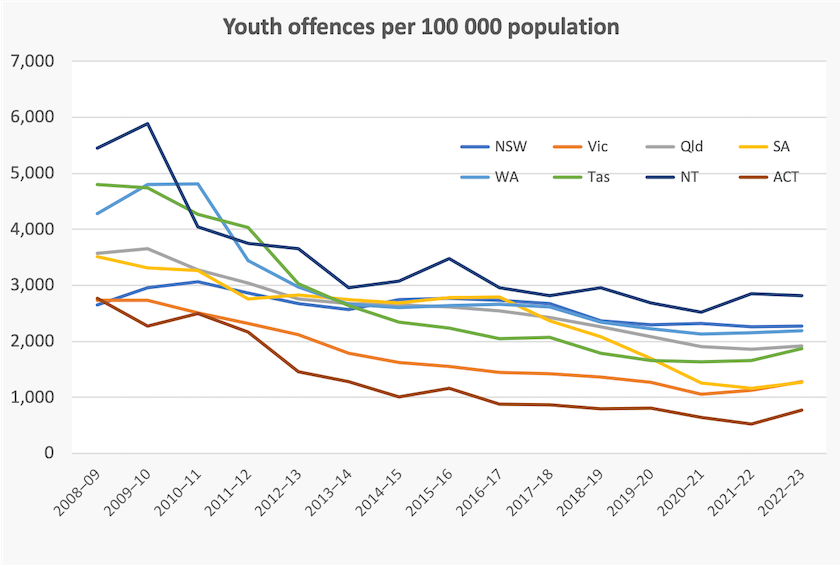

No, youth crime isn’t rising. Although some states have seen a small uptick, over the longer term youth crime is actually falling or flattening out in all states and territories, including Queensland and the Northern Territory.

The ABC’s Kenjo Sato has brought trends in youth crime to our attention, drawing on work by criminologist Renee Zahnow: Criminologists debunk claims of “youth crime crisis” as data shows dramatic declines. The basic data, drawn from readily-available sources, is shown in the graph below. Zahnow, drawing on more detailed data, suggests that the decline in youth crime may be even more significant than these numbers suggest. In Queensland at least, reported youth crime may have risen because of better police responses.

So why the fuss? How was the CLP in the Northern Territory able to ride into office on a law’n’order agenda, focussed on youth crime? How come the Queensland opposition has a similar focus, with its “Adult crime, adult time” campaign?

Zahnow blames the usual mischief-makers for the misconception -- sensationalist news outlets, social media platforms, and political opportunists. The Coalition has never let evidence stand in the way of a crime scare campaign.

Part of the answer lies in the concentration of youth crimes in a few locations – rural cities serving as commercial and government centres for large rural regions.

More specifically there is the nature of the crimes in these cities: they’re showy, they make for vivid television footage, and they’re so stupidly aimless. We might have some understanding when a kid steals money, booze or cigarettes, but what benefit is there for kids in writing off a Landcruiser or causing $100 000 damage to a business? The crimes that have come to our attention are those of young people who seem to have no stake in society.

Another factor raising the political prominence of youth crime is that police, the victims and the communities perceive, rightly or wrongly, that there are no consequences for these children’s destructive behaviour. Public annoyance intensifies when a serious crime is committed by an offender or a suspect who been released on bail. One prominent case in the Northern Territory is the murder of a 20-year old bottle-shop worker who was murdered by someone who was out on bail. In response the Labor government tightened bail laws, and the present government is going further, including lowering the age of criminal responsibility.

Sociologists and criminologists have responded to these tough-on-crime moves by pointing out that such responses to youth crime don’t work, and in fact are counter-productive. The behaviour of indigenous children engaged in crime is shaped by generations of racism and poverty. Neglect, family violence and a lack of liveable housing, are all contributing factors. Locking up children in prison only worsens the problem in the long term. A prison is the worst environment for children whose brains are still developing: imprisonment is almost an assured precursor to an adult life of crime.

The situation in the Northern Territory, specifically in Alice Springs, is explained in a Saturday Paper article by Daniel James: The post-Intervention plight of Alice Springs. He explains that dysfunctional behaviour in the Northern Territory can largely be explained by previous tough-on-crime policies, particularly the Howard Government’s National Emergency Response in 2007 – “The Intervention”. More of the same won’t work. To quote James:

The overall tension, the push for punitive short-term measures to solve ingrained complex problems, will probably work for a while if success is gauged against simple metrics such as arrest and incarceration rates.

If you don’t have a Saturday Paper subscription, or if you have exhausted your paywall-free access, you can hear James on the Schwarz Media 7am podcast: This is Alice Springs: children of the Intervention.

Right-wing political opportunism has brought us to this dismal point. But those calling for reform bear some responsibility for this outcome, because they have allowed the options, in the public mind, to become a choice between “be soft on the little dears” and “lock-em-up”. That’s sort of binary choice is manna for right-wing media. Serious social researchers don’t advocate letting undisciplined kids roam the streets causing havoc, but they are not necessarily the people who have the attention of journalists.

Those calling for reform have given little acknowledgement to the harm these young people cause, not just to individuals and businesses, but to entire communities. The public are not callous: in fact most people of Alice Springs understand how miserable these children’s lives are, and have generally shown forbearance over the years. But no-one has been offering solutions that protect communities while attending to children’s interests without putting them in jail. No wonder they express their frustration at the ballot box.

Solutions that attend to children’s interests while protecting communities would inevitably be expensive, but in the long run they would probably be far less costly than the tough-on-crime response. Their cost would be a small ongoing imposition on the wider community whose past policies have brought this situation about.