Other politics

Democracy isn’t working – the EIU Democracy Index

Australia scores well on the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index 2024. As one of the world’s “full democracies” we come in at #11, up three places from 2023, which in turn was up one place on 2022. Ahead of us are a clutch of Nordic countries, New Zealand, Switzerland, Ireland and Luxembourg.

Only 6.6 percent of the world’s population live in the 25 countries classified as “full democracies”. Notably America (place #28), once the world’s inspirational model of democracy, isn’t one of them. Nor is Israel (#31), once held out as a contrast to the authoritarian regimes of its surrounding neighbours.

Ranking and classification are only part of the EIU’s task. The main concern is a worldwide continuing fall in four of their five categories of democratic health – “civil liberties”, “electoral processes and pluralism”, “functioning of government”, and “political culture”. In the fifth category, “political participation”, there has been an improvement, but this could simply indicate that people are expressing discontent with other aspects of democracy.

The report’s overview has the confronting headline “Democracy isn’t working”. To quote from that overview:

The focus of this year’s report is why representative democracy is not working for large numbers of citizens around the world. There is a growing consensus that the democratic model developed over the past century is in trouble, but there is less clarity about why people are so disenchanted with their democracies. In 2024, when countries inhabited by more than half of the global population went to the polls, popular disaffection with the performance of government was expressed in an anti-incumbent backlash and rising support for populist insurgents.

There is a tendency for some commentators to see this populist insurgency as the core problem, but the report’s authors see it as a consequence of deficiencies that have arisen in representative democracy:

That democracy is not working well in many of the world’s democracies has been clear for some time. The rise of populist political alternatives over the past decade is an expression of a problem with the mainstream parties that have been in power for the past 75 years and the political systems they have developed. There is nothing undemocratic about new, anti-establishment parties challenging the status quo, as long as they do so by democratic means. They may not appear to have all the answers to the pressing issues of our time, but they are at least connecting with marginalised sections of the electorate and meeting a demand for representation from citizens who feel that they do not have a voice. [Emphasis added]

Independents are making their mark

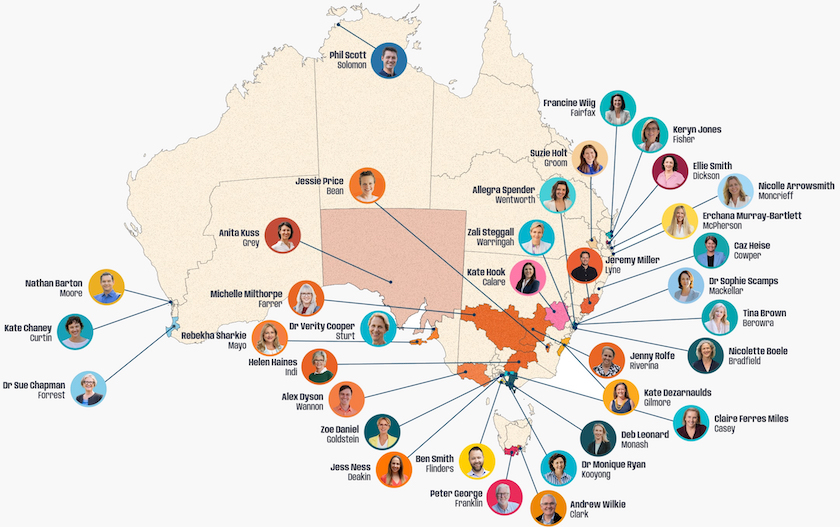

Copied from the Climate 200 site

Notice something odd about the opinion polls – something the media are missing?

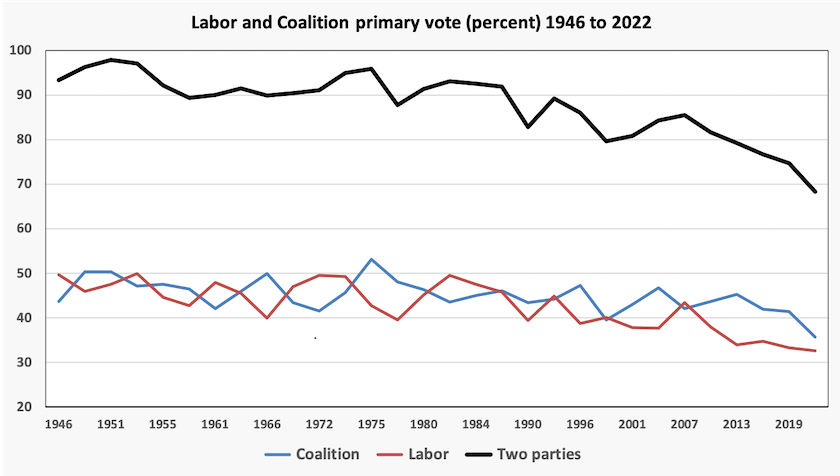

It’s the anaemic performance of the Labor plus Coalition duopoly – down to 65 percent in the most recent national poll, conducted by YouGov on February 21 to 25. Among the rest, the Greens are polling at 14 percent, One Nation at 8 percent, and “Other” at 13 percent.

For reasons to do with sample size, polls tend to be least accurate when they are ascertaining support among smaller parties, but that 13 percent is a strikingly high figure. YouGov estimates that after attributing about 3 percent to Clive Palmer’s Trumpet of Patriots (it’s really called that) and to other obscure parties, support for independents is around 10 percent nationally.

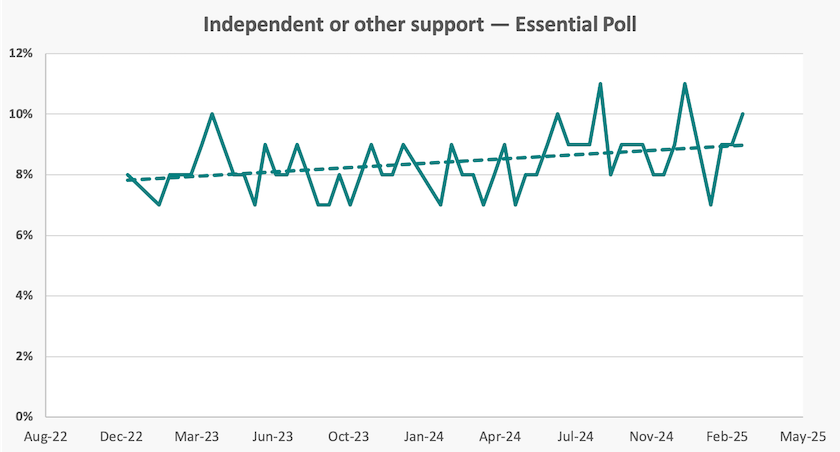

Similarly Essential has been polling “independent or other party”, separately from United Australia and One Nation, for two years. Unsurprisingly there is a fair bit of noise in the time series, but there is a definite upward trend, shown in the graph below.

Support of 9 to 10 percent isn’t going to get anyone elected, but serious independents are not standing in all seats. Climate 200 has listed 35 community independents who will be running strong campaigns with a reasonable amount of financial backing. To these should be added Bob Katter who should easily retain Kennedy in far-north Queensland, and Dai Le, who will be running again in Fowler in western Sydney. There are also two Coalition MPs who have quit their parties and are running as independents – Russell Broadbent, formerly of the Liberal Party, re-contesting Monash in Gippsland, and Andrew Gee, formerly of the National Party, re-contesting Calare in central-western New South Wales. (Monash is also being contested by independent, Deb Leonard and Calare is also being contested by independent Kate Hook: expect some interesting four-way contests.) That means there will be around 37 strong campaigns in the 151- member House of Representatives, or in about a quarter of all electorates.

If support is concentrated in the same proportion, that means on average independents will be getting 35 to 40 percent of the vote, which in rough terms is enough to get them over the line in electorates with weak Labor support.

Julia Zemiro (whom we may remember as an actor in Bell’s Shakespeare company, or later as a television producer) has a website of half-hour podcasts from 16 independents, and the ABC’s Jane Norman has a post Inside the community independents movement targeting key marginal seats at the next federal electiondescribing how community independents organize their campaigns. Climate 200 is one source of consolidated funding, and there are other outfits pulling funds together, particularly for non-metropolitan electorates. Also there are other movements willing to give independents campaign support.

Jane Norman notes that some political observers assume that support for the main parties will recover, because the independent surge in 2022 was a particular reaction against Scott Morrison. It’s true that Dutton isn’t another Morrison, but he has his own political liabilities – his party’s ridiculous energy policies and his personal adoption of Trump’s campaign tactics.

A good idea from the Greens in response to “New public management”

Remember the Commonwealth Employment Service – the CES? Offices in the suburbs and in country towns, linking employers to job seekers, staffed by public servants.

The Greens want to re-establish the CES. It would be staffed by Centrelink officers, replacing the “costly, ineffective and cruel” for-profit privatised employment services. It would also abolish onerous and degrading mutual obligation requirements. Unsurprisingly the Community and Public Service Union supports the Greens’ proposal.

The Greens draw on the recommendations of a House Select Committee Report on Employment Services, commissioned shortly after the present government came to office. It was critical of the harsh and inflexible way mutual obligation was applied, but it recommended reforming its reporting and compliance rules, rather than abolishing it as the Greens are suggesting.

Nor did it recommend a complete takeover from the private contracting model, but it was highly critical of the separation between public servants overseeing employment services and the private entities providing services. Such separation is commonplace in the contracting model adopted by many Commonwealth departments and agencies.

It was also highly critical of reliance on free-for-all competition among service providers and the supposed benefits of “choice” – another fashion adopted uncritically in human services. It wrote:

It should not be controversial to conclude that that full marketisation has failed. The failures of the current outsourced quasi-market system, driven by neoliberal New Public Management theories that have exhausted their utility, have been identified repeatedly by experts and analysts. The costs of the system are not properly acknowledged.

The level and nature of competition is excessive and counterproductive, resulting in high levels of service saturation, fragmentation, and duplication yet without specialisation or localisation. In numerous regional towns and disadvantaged suburban centres, it seems there is a service provider operating on every street block, providing largely the same service with little innovation or variation in offerings or performance. Coupled with the myriad of Disability Employment Services (DES) providers it is a ridiculous situation.

The government adopted some aspects of the committee’s recommendations, mainly around the administration of mutual obligation, and a refinement of the one-size-fits-all approach, but it doesn’t seem to be committed to building “a new Commonwealth Employment Service System” as the committee recommended.

The government should listen to the Greens on this one

The Greens are on to something that the government is missing. That is the reconnection of public servants with the people who, through their taxes, pay their wages, and whom they are serving.

A new CES may not have a replica of the old CES offices – technology has moved on – but the important element of that old system was people’s connection with their government. The people who worked in the CES cared about attending with job seekers. In the world of New Public Management, however, the job seeker is dealing with someone driven to comply with a set of performance indicators – indicators knocked up in a deal between administrators concerned with impression management for their ministers, and profit-motivated private businesses operating in a sham market.

New Public Management is a 1980s fad with no rigorous basis. It was knocked together by ideologues who believed that idealized private sector models taught in Economics 1 classes could be applied to the full range of government activities. It infected university schools of public administration, and was enthusiastically adopted by governments holding the neoliberal idea that the private sector is intrinsically more competent than the public sector, particularly in the English-speaking world.

It arose out of naivety and ignorance rather than malice, but its effect was to make a mockery of the idea of “public service”, and to contribute to the idea that government is a self-serving institution, attending to the interests of elites isolated from people’s real lives.

Whatever specific merits or problems lie with the Greens’ specific CES idea, its main contribution has been to call out the dysfunctionality of the “New public management” idea, and to state the case for a re-establishment of the idea of public service.

Small beer

Free beer for all the workers, When the red revolution comes

Well, not quite free beer, but one could hardly classify the Albanese government as “red”.

The government announced that it will drop indexation of the excise on draft beer for two years. Unsurprisingly the Australian Hotels Association has welcomed the move – but would like the government to do the same for all alcoholic drinks.

It’s a strange move for a government holding an election in a tough fiscal environment. It won’t take effect until well after the election, and it won’t result in a price reduction: rather it will be an unnoticed price rise that doesn’t happen. And even that is trivial – about one cent a “pint” (a quaint AHA term for a 570 ml glass).

Politically it confirms the impression that while the Albanese government is helping out with small moves to deal with day-to-day cost-of-living problems, it is neglecting broader structural issues. That impression may not benefit the opposition because it is even less engaged with economic structure, but it contributes to the idea that established political parties work within a comfort zone of timid incrementalism, while kicking bigger problems down the road.

Possibly it’s an attempt to drive a wedge between the Liberal Party and the National Party. Last year David Littleproud floated the idea of freezing beer excise, but Liberal party finance and treasury spokespeople knocked him back.

Possibly it’s a signal to the Reserve Bank that the government is prepared to hold back on measures that contribute disproportionately to the CPI, but while there have been high price rises in “alcoholic beverages” as defined by the ABS, that has been mainly for wine: the price of beer has actually risen more slowly than the CPI in recent years.

Possibly it’s because when the regular six-monthly indexed rise in excise kicked in on February 1, sensitivity to the issue was heightened.

Less attention has been given to another concession as part of the package. There is presently a remission of all excise up to $350 000 a year: this will rise to $400 000. That’s of some help to craft brewers, but only to small ones: if excise is about $2 per liter the concession applies to only about the first 200 000 liters. Nevertheless the concession may provide an opportunity for Albanese to be seen enjoying a craft IPA rather than a VB in a photo opp. That may go down well with urbanites.

The issue the government is avoiding is the concentration in this industry. Two foreign-owned companies command 85 percent of the beer market – in fact about 90 percent of the “mainstream” market. You can hear an episode of The Money – Market Concentration of the Beer Industry – broadcast last year, explaining the market structure of the beer industry, how the big brewers hold on to their position, and what it means for drinkers. (29 minutes). You will also learn the meaning of the term “craftwashing”. Industry concentration should be a matter of competition policy rather than small fiddles with levels of excise.

This case is symptomatic of a government, elected to clean up the mess left by nine years of the Coalition’s lazy economic management, that has been spooked into excess caution by its interpretation of history. According to that interpretation, past Labor policies have been too adventurous and have scared the electors. As the ABC’s Jacob Greber writes, Anthony Albanese might be wary of voter backlash but there's a cost to doing nothing.

Polling – socialism is back in fashion

The latest Essential poll has eight sets of questions on our political attitudes and behaviour.

Election voting method. Only 35 percent of us plan to vote at the polling station on election day, continuing an established move to pre-poll voting. Postal voting too is losing popularity. This has clear implications for the timing of costings of election promises.

Voting firmness. By now half of us say “I know who I will vote for and will not change my mind”. Coalition voters are firmer in their intentions that other voters, and older voters are particularly fixed in their intentions.

Election engagement. About half of us have been paying at least some attention to the election. Coalition voters and older voters have been paying more attention than others, and men have been paying more attention than women.

Likely election outcome. Most respondents believe there will be a majority government. Most Labor voters believe it will be a Labor majority government, and most Coalition voters believe it will be a Coalition majority government. This says something about the extent to which we pay attention to opinion polls.

Impact of interest rate cuts. Unsurprisingly we like interest rate cuts. We think they will be good for the economy, even though we don’t think they will do much for us personally. This is consistent with the proposition that it is only a minority who are struggling under the burden of high interest rates, rather than the idea that we are all suffering a “cost of living crisis”.

Interpretation of the interest rate cuts. The government will be disappointed to learn that 56 percent of respondents believe that “the interest rate cuts are too little too late and show that the government’s approach to economic management is not working”. There are predictable partisan divisions on this question. Contrary to the general belief that interest rates are all about the burden of mortgages, people with and without mortgages give the same response. People with “investment” properties, however, tend to welcome the cuts.

Most trusted party on issues. On a set of economic issues, Labor generally comes ahead of the Coalition. Labor is particularly strong on funding Medicare, supporting higher wages and addressing climate change. On trust to “manage the economy” and “manage international relationships” Labor and the Coalition are about equal: that’s surprising in view of prevailing assumptions about the Coalition’s dominance on these matters.

Attention ratings. Respondents are asked how much attention they pay to “my personal” connections, “national issues”, “world affairs”, “state issues”, and “my local community”. All except “my personal connections” score below 20 percent. Are we really so turned off?

The YouGov poll that tracks voting intention has a pair of supplementary questions about our attitude to the government taking over the Whyalla steelworks, and running them as a public company. We like the idea: 60 to 62 percent “support”, and 8 to 9 percent “oppose”. There is little variation by people’s voting intention.

This is no longer the world in which the Coalition is able to use the word “socialism” as a term of abuse.