Economics

The budget will have a deficit: that’s good economic management

Did the Queensland floods force Albanese to abandon his plan for an April 12 election, or did it give him a good excuse to delay it to early May – probably May 10?

We will never know unless at some time he publishes his political memoirs.

That means the government will be presenting a budget in ten days’ time, on Tuesday March 25. It probably has more leeway for a mildly expansionary budget than would have been imagined late last year.

The fiscal outlook, revealed in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO), published in December, pointed to a cash deficit of $27 billion in the current financial year, rising to $47 billion in 2025-26 – around 1.0 percent of GDP this year and 1.6 percent of GDP next year. That’s remarkably low in comparison with other countries. Fiscal deficits are 6.6 percent of GDP in the USA, 4.5 percent in the UK, and our deficit is even lower than Germany’s 1.8 percent – a country renowned for its fiscal austerity.

But such are Australian politics that deficits are seen as “bad”, and surpluses are seen as “good”. The fiscal outcome has become an indicator of governments’ economic competence, a point stressed by Sydney Morning Herald journalist Gary Newman in his article Labor can’t manage the economy, right? The claim by Dutton and co doesn’t stand up.

Chris Richardson points out that our deficit for this year will actually be about $11 billion smaller than was calculated in the MYEFO. Tax collections are up, because of fiscal drag in income taxes (nominal income rises interacting with progressive tax scales) and because employment numbers are higher than predicted in the MYEFO.

Also, with the looming possibility of a US recession resulting from the Republicans’ economic idiocy, this is not the time for economic austerity.

Besides a set of already-announced election promises to do with health care, school education and certain infrastructure projects, there will be pressure to lift defence spending – either in response to America’s demand, or in recognition that we need to treat the US as an unreliable ally. In view of the Australian Energy Regulator’s signal that electricity prices will be rising (coal and gas are expensive ways to generate electricity) the government will almost certainly have to extend electricity bill subsidies.

The usual trifecta of economic indicators – inflation, employment and growth – is pointing in the right direction for a government preparing a budget. The inflation inherited from the Coalition government is back under control, the labour market is strong, and if the GDP growth in the December quarter is maintained, economic growth will exceed MYEFO forecasts.

That traditional trifecta of course leaves out housing affordability, and it reveals nothing about the distribution of income. What counts politically is the economy as people experience it when they go shopping or try to buy a house. About a third of Australians, including young people unable to become home owners, home owners with high mortgages, and people on social security payments, are facing financial hardship. Even though that hardship results from decades of the Coalition’s economic incompetence, the political message “are you worse off than you were before Labor was elected?” has traction.

In the government’s favour, however, people are feeling a little better off following the tax cuts that came into effect last July, and the February interest-rate cuts are starting to be noticed. It’s not so much the effects on people’s pay packets, as a feeling that the economy has turned the corner, or is back on track, to use the common clichés. Indexes of consumer confidence have been rising rapidly, and perhaps we’re not hearing so many journalists talking about “a cost-of-living crisis”.

The more serious problem facing the government is that in presenting a budget before an election it will be unable to do anything more than to tinker around the edges of tax reform. We need to collect more revenue, and we need the distribution of taxes to be much fairer. Tax reform has now been delayed for another year.

The economic case for increasing JobSeeker payments

Politics 1 students would say that it is politically idiotic for a government facing a tough fiscal forecast to go into an election promising to increase unemployment benefits, but that is what the government’s Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee has just recommended.

Its main recommendation is that the base rate of JobSeeker be substantially increased. Its other nine recommendations relate to indexation of benefits and improvements in rent assistance, remote area allowances, and child care – the set of programs some would classify as distributive welfare without economic benefits.

It details the improvements in recipients’ lives that would result from an increase in JobSeeker, confirming the benefits they enjoyed while allowances were temporarily increased during the pandemic, documented by the e61 Research Institute.

Importantly, for economic hard-heads, it finds there would be a net economic return from increasing the Jobseeker payment, and by extension from improving other benefits:

The research found considerable economic and social benefits from improving the adequacy of the JobSeeker Payment. The research found that such an increase would create long-run benefits to Australia from a healthier and more productive workforce and decreased spending on government services worth $71.8 million, estimated for a representative group of 20,000 JobSeeker recipients. This is a return to society of $1.24 for every dollar invested. Importantly, the long-run benefits far outweigh any potential costs from reduced work incentives due to an increase in JobSeeker.

In fact, contrary to the assumption that an increase in JobSeeker benefits would result in reduced work incentives, in their submission to the committee e61 pointed to evidence suggesting that in spite of the high effective marginal tax rates for those going from social security transfers to employment, increasing Jobseeker payments would result in no disincentive to work.

On Radio National there is a 5-minute interview with labour market economist Jeff Borland, a member of the committee, explaining the economic benefits of increasing Jobseeker payments.

Cassandra Goldie of ACOSS, who is also a member of the committee, has another segment on Radio National, stressing the inadequacy of Jobseeker’s $56 a day payment. (4 minutes). She also has a slightly longer segment on the ABC’s 730 program, contrasting the government’s toughness on Jobseeker recipients with the generosity of the tax cuts to those with high incomes.

The government has given no indication that the coming budget will see a rise in these benefits. The challenge, as usual, is that many of these benefits would be realized outside the one-year of the budget and the three years of its extended estimates, and that many benefits would be in the form of economic benefits that do not show up in fiscal accounts. Unless the government can manage to shift the public’s attention away from short-term fiscal management (managing a bank account), which is the way the Coalition sees the budget, and towards economic management, it will be politically hard for the government to raise benefits.

HILDA exposes Australia’s worsening wealth inequality

The annual report from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA) was published this week.

HILDA data shows income inequality is at a 20-year high is the headline in the Conversation article by Ferdi Botha of the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, summarising its findings.

Not only is income inequality rising, but also wealth inequality is rising. Older Australians, particularly those aged over 65, have enjoyed a rapid rise in wealth. Some of this is explained by high rates of home ownership among older people: HILDA presents detailed data on declining rates of home ownership, particularly among young people.

Older people have also enjoyed a huge growth in financial wealth, shown in HILDA’s table of superannuation balances by age. HILDA also provides some data on inheritances: the number of people receiving inheritances and the size of those inheritances has been rising steeply.

These are significant findings, because wealth inequality is more entrenched than income inequality, and once people accumulate a certain level of financial wealth it can go on growing through re-investment. Policymakers and welfare lobbyists tend to focus on income inequality, but the serious challenge to Australia is wealth inequality.

HILDA also provides data on gambling, confirming that most Australians do not gamble at all. Around 30 percent buy lottery tickets, but fewer than 10 percent of Australians engage in other forms of gambling – poker machines, sport betting and so on. Those who do spend on these activities spend heavily. There is a growing incidence of problem gambling, particularly among men.

HILDA covers far more than financial data. Attention is often drawn to its data on the distribution of housework and evidence that men are still not pulling their weight. Religious affiliation and observance, community participation, and even pet ownership are also covered in its surveys.

There is a link to the HILDA report on the Conversation article. Or you can download the 210-page reportdirectly. Note that for the most part it covers the period 2001 to 2022, ending at a time when inflation was high and the country was getting over the shock of Covid-19.

Mind the gap – it’s not closing

The Productivity Commission has produced its Closing the Gap update. On only 3 of the 14 indicators for which the Commission has reliable data, are outcomes on track. The table below is taken from the Commission’s “dashboard”.

The ABC has a short summary of the report, and comments from people involved in indigenous policy. It also has some of the data disaggregated at a state and territory level.

If you want a better paid job, head to the bush (conditions apply)

Canowindra welcomes the huddled masses yearning to breathe free

The Regional Australia Institute has compared incomes in our cities and in other locations, detailed in a report Beyond city limits: unveiling income premiums in regional Australia.

They use five categories of regions, in line with ABS classifications of LGAs:

- Major cities – Canberra, five state capitals, and 12 mostly coastal major urban areas including, for example, Gold Coast, Geelong, Maitland;

- Inner regional – Hobart, and 14 cities or densely-populated LGAs including Albury, Bendigo, Wagga-Wagga;

- Outer regional – Darwin, and 15 smaller cities or densely-populated LGAs, including Broken Hill, Port Augusta, Burnie;

- Remote – Alice Springs, Broome, Coonamble, Dalwallinu, Esperance, Katherine, Port Lincoln;

- Very remote -- Barkly, Blackall Tambo, Carnarvon, Exmouth, Flinders, Streaky Bay.

The report is upbeat about the prospects for “regional” Australia, To quote from its summary:

Many Australian regions have experienced substantial population growth since the COVID era. Migration to our regions is still 1.8% above the average levels during the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns and more than 20% higher than pre-COVID levels. This has led to stronger job markets and higher wages in regional centres.

It goes on to attribute this to lower housing costs and opportunities for remote working.

But its findings do not suggest there are significant enticements for people to move out of big cities.

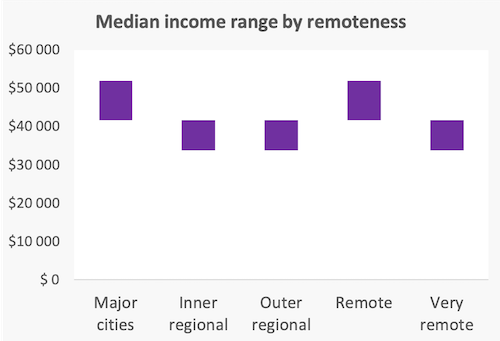

The general finding is that incomes in the major cities are matched only in “remote” regions, as shown in the graph below (before controlling for age, gender or occupations).

For technicians, trade workers, machinery operators and drivers, workers in remote and very remote regions enjoy significantly higher incomes than workers in major cities. For most other occupations, however, incomes outside major cities tend to be much the same as incomes in major cities. In fact professionals have significantly lower incomes in inner and outer regional areas than they do in big cities: this is probably a reflection of broad classifications, because a surgeon and a GP would both fall into the same “professional” classification, for example.

Remote regions accommodate only 2 percent of our population. If pressure on our big cities is to ease, movement will be to the “inner” and “outer” zones, which between them accommodate 26 percent of our population.

The Institute uses the report’s findings to call for a number of policy nudges to entice people to move out of big cities, or to encourage immigrants to skip over the big cities when they come to Australia. Such nudges could include information campaigns, easier visas for immigrants who choose to go bush, improved digital connectivity, and investment in housing, housing, health and education services.

These are all well-researched measures and they make economic sense, because in terms of required public investment the marginal cost of providing for one more person in a small city is far less than in our big state capitals.

But these nudges, in themselves, may not be sufficient to encourage a shift in the population. One revelation in this report is that teachers and health workers earn less in inner regional areas than they do in major cities. If families are to be attracted to these places, they need to be assured that there are good health services and that their children won’t be disadvantaged by a lower standard of school education than they would enjoy in the big cities. If state governments want our country cities and towns to thrive, they must ensure that schools are at least as good as they are in the big cities.

Also, studies on reasons people do and don’t move show that access back to major cities is an issue in people’s personal and business choices. Airfares connecting our smaller cities to our capital cities are absurdly high, country train services are almost non-existent or very slow, and apart for settlements along the Brisbane – Melbourne freeway, roads back to state capitals are narrow, congested and dangerous. Too often “decentralization” policies have neglected the need for transport links back to the big cities.

Productivity matters

Links to articles on productivity have been a frequent feature of these roundups, covering a wide range of views, from ideas that productivity is meaningless, through to the more conventional view that improved productivity is a necessary condition (but not a sufficient condition) for wage growth in the long term.

Michael Plumb of the Reserve Bank has delivered a data-rich paper Why productivity matters to the Australian Business Economists Annual Forecasting Conference. Its title reveals its viewpoint, but avoids making a simple pitch for improving productivity. It goes into the difficulty in estimating changes in productivity in the care sector – difficulties that are bound to become more significant over time as that sector grows relative to the rest of the economy.

The paper also goes into the way economy-wide indicators of productivity, such as the commonly-used index of GDP per hour worked, are influenced by changes in terms of trade, an issue of particular relevance for Australia whose GDP is sensitive to changes in commodity prices. A rise in the world price of iron ore or gas, for example, will increase GDP per hour worked, even if there is no change in work practices or new capital investment.

Labour productivity stopped growing about ten years ago, and if we look through the weird figures associated with the pandemic, it seems to have been flat since. This flattening is associated with a slowdown in capital investment. With the risk of a Trump-induced trade war, and the risk that a Dutton-led Coalition government may be elected, the outlook for capital investment is uncertain. Global uncertainty is our next challenge writes Lisa Toohey of the University of New South Wales in The Conversation.