Other public policy

Immigration

One of the few policy areas where the voting public give the Coalition a lead on Labor is immigration.

In many countries – the USA, Germany, the Netherlands – proposals to cut immigration have helped populist right-wing parties gain support. A promise to cut immigration is a neat dog whistle to racists, and it is easy to link immigration to rising real-estate prices and pressure on infrastructure, schools and other government services.

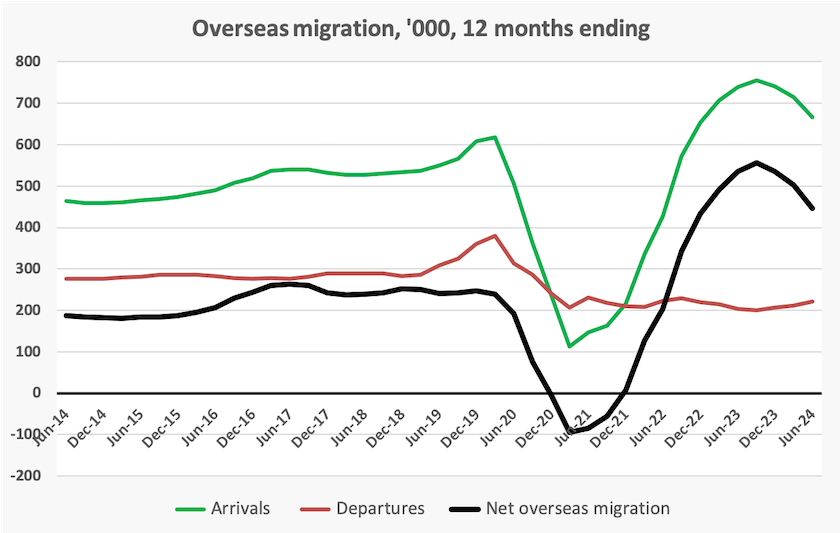

It is also easy to lie about immigration, particularly in Australia, where we had a large surge catching up with a backlog after the Covid-19 restrictions. Those movements are shown in the graph below, taken from the ABS annual overseas migration data.

As Abul Rizvi explains in Pearls and Irritations – Immigration policy and the federal election – the other way to misrepresent immigration is to fail to distinguish between numbers allocated in Australia’s migration program, and net migration (the figures shown on that graph). Net migration includes people entering under the migration program, and all other movements, including Australians coming and going.

Governments have control only over the migration program, which accounts for a small proportion of our net migration, over most of which the government has hardly any control.

Australians come and go, depending on conditions in other countries. The Government’s Smart Travellerwebsite reports that there are about a million Australians living overseas. That includes about 100 000 living in the USA, some of whom will come home in response to the political and economic chaos in that country. Also there is essentially no migration control between New Zealand and Australia. Following election of a right-wing government in late 2023, whose austerity policies plunged the country into recession, many New Zealanders have been coming to Australia to find work.

It is net migration that influences demand for housing, which means that it is disingenuous at best, and outright deceptive at worst, for Dutton to accuse the government of letting immigration run out of control, or to blame immigration for our housing shortage.

Dutton has proposed to cut the migration program from 185 000 to 140 000, but Rizvi believes that if elected a Coalition government would find it hard to meet even that modest target, because there are many pressures from employer groups and the National Party to sustain high immigration. In fact, as Rizvi points out, Dutton has his own proposal to re-introduce a golden ticket visa modelled on the one Trump recently introduced.

But one area where governments have firm control is in student visas.

Capping student numbers

Student dorm AU

Education is one of our most successful export industries. So it’s strange to see that both the government and the opposition are proposing to cap foreign student numbers, just at a time when it’s clear that Trump’s tariff policies will put a big dent into our earnings from mineral commodities.

Writing in The Conversation Andrew Norton of Monash University explains the government’s and the opposition’s policies on student visas: The Coalition has announced an even more radical plan to cut international students than Labor. Here’s how it would work. Both the government and the opposition want to impose caps on foreign student numbers, and higher visa application fees. The opposition’s caps are tougher and their visa fees are higher – $5 000 for students enrolling in one of the Group of Eight old universities, $2 500 for other universities.

The ABC’s Maani Truu reports that the university sector sees the Coalition’s plans as straight out of Trump’s playbook.

It is hard to see how capping student visas could ease pressure on housing. The ABC’s Conor Duffy reports on research by Flinders University academics, which could find no independent relationship between international student numbers and rental costs. That’s hardly surprising. Student dormitories that have sprung up around our campuses are specifically built for students. While the more recently constructed ones have ensuite bathrooms, with their shared kitchens and laundries, they are hardly in competition with housing for the general population. As for off-campus accommodation, this is usually of a low standard. Letting an old house to a group of engineering students saves on demolition costs.

We need a serious debate on population

The Coalition’s attempts to weaponize immigration policy has put off, once again, any serious consideration of immigration policy. Our immigration policies seem to result from an implicit compromise between lobbies for high immigration, and community concerns about pressures on housing and infrastructure and some people’s anxieties about the sustainability of multiculturalism.

Most independent commentators seem to accept this compromise as a given condition, but not everyone. “Re-examining a high population growth model” is one of five economic themes that will dominate the next Parliament in a paper prepared by the e51 Institute in collaboration with the University of New South Wales.

Perhaps its title is a misnomer – “Five economic themes that should dominate the next Parliament” would be a better title, because its four other themes include matters neither of the old, established parties really want to address, including “achieving a sustainable intergenerational bargain”. (Gareth Hutchens summarises and comments on all five aspects of the report.)

On population growth the e61 report does not make any specific recommendation, but it draws attention to the tension between having one of the “developed” world’s highest rates of population growth and our established pattern of dealing with population growth in our large cities with detached housing.

And we do need a re-think about student numbers. The current government (without support from the opposition), has cracked down on shonky private education establishments operating as de-facto paths to immigration. We should also ask if a financing model that relies on foreigners cross-subsidizing domestic students is sustainable, and whether the experience of foreign students is contributing to or detracting from our soft power.

Violence against women and children: many causes, a broad policy approach needed

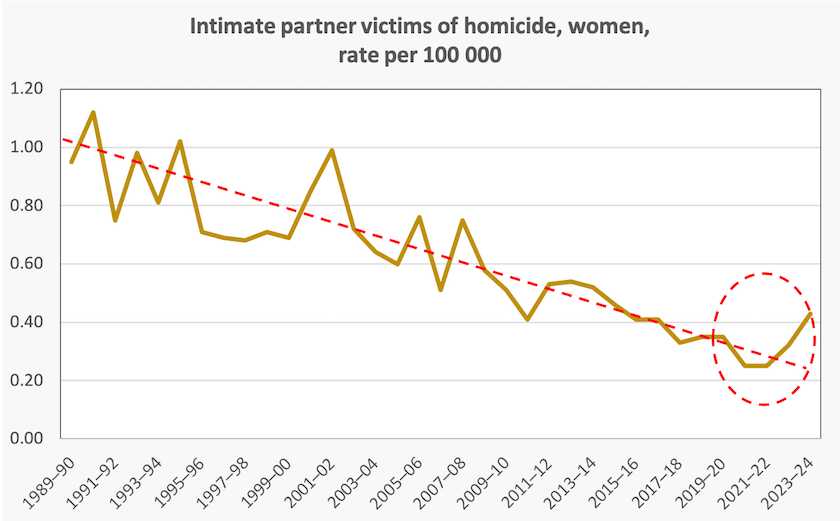

There are three ways to look at the graph below on intimate partner homicide, constructed from homicide datacollated by the Australian Institute of Criminology.

One is to focus on the trend line. That’s an impressive reduction – from 1.0 to 0.2 per 100 000 adult women. Many problems in public health and safety, such as motor vehicle fatalities, show such a pattern – years of improvement until a core of hard cases remains, on which progress is really difficult.

Another is to look at recent data, which can be used to write a headline “Murders of women and children up 80 percent in two years’’. That has indeed been a strong media story in recent times and there is speculation about the causes: financial stress and social media valorising aggressive masculinity often get a mention.

A third is to dig deeper into the issue. Because of variations in the way crimes of domestic violence are reported and an increased tendency for such crimes to be reported, it is difficult for policymakers and researchers to be sure about trends, but they use homicide as an indicator, which is pretty well free of such a bias. But what if it has become a poor indicator? Maybe because of faster intervention by police, or better emergency care, more women subject to extreme violence are surviving.

Jess Hill in her Quarterly Essay Losing it, can we stop violence against women and children? goes into all three questions, drawing on every piece of evidence she can lay her hands on. It is a model case study in policy analysis, and a guide to where policymakers should direct their attention.

Because domestic violence has an intergenerational element – many men who inflict violence on their partners and children have themselves been victims of domestic violence in their own childhood – Hill stresses the need for improved services for troubled children as a way to break the cycle. We spend a vast amount of public money on these children through social security, social support and law enforcement, with miserably poor results. There has to be a better way.

She notes the contribution of alcohol and gambling to domestic violence and the influence of these industries on policymakers, while leaving open questions about the extent to which they are causal variables or simply correlated variables. Similarly she observes the manosphere movement on social media, asking if it is a driver of misogyny or if it is simply performative?

She draws attention to concentrations of domestic violence, particularly in some indigenous communities, and to a disturbing trend that sees the average age of perpetrators of sexual violence becoming younger.

She writes about two distinct streams of thought among policymakers and researchers. One is the idea that domestic violence will be largely eliminated as we make progress towards gender equality: public policy should therefore be directed to closing gender gaps. The other is concerned with specific contributing factors – social disadvantage, inequality, addiction to gambling, alcohol and other drugs, and mental illness. She finds the division unhelpful: a choice does not have to be made because one effect can have many causes, and policymakers can forget that conditions that are necessary are not always sufficient to achieve progress.

Public policy can move on both fronts. Janeen Baxter of the University of Queensland, writing in The Conversation, notes that despite some key milestones since 2000, Australia still has a long way to go on gender equality.

Hill provides strong arguments that governments, particularly state governments, need to do a complete reconstruction of child services, and that all governments need to rein in the influence of the alcohol and gambling industries.

Don’t go for one grand policy, but use lots of measures that work.