Away from the fading duopoly

Australia’s changed political landscape

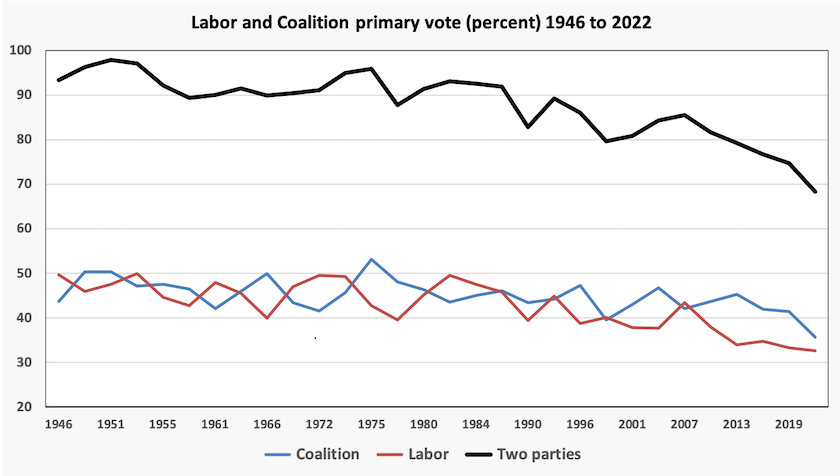

It’s nauseating to hear journalists using terms like “bipartisan” and “both sides of politics”, as if we’re living in the Australia of 1951, when the combined primary vote of Labor and the Coalition was 98 percent. We don’t know much about the other 2 percent – communists perhaps?

In our last federal election the combined primary vote of Labor and the Coalition was only 68 percent. It could well be lower in this election: the latest Essential poll puts their combined vote at 63 percent.

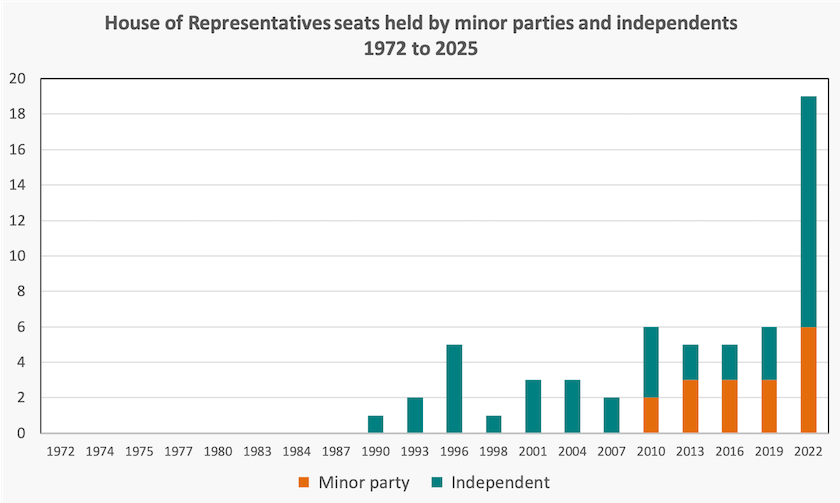

It has taken a long time for the rise in support for independents and minor parties to show up in terms of winning seats in the House of Representatives. The general story in the media is that 2022 saw a sudden rush of support for “teal” independents, but their electoral success was a manifestation of a movement that had been building up for many years. The process isn’t linear; rather it’s like a dam bursting after a long period of a slowly rising water level.

Casey Briggs and his colleagues from the ABC Story Lab have an excellent infographic describing this process: Over five decades, here’s how voters have shifted away from the major parties. The present situation is shown in the graph below.[1]

While some of his journalistic colleagues talk about a “hung Parliament”, a term that has suggestions of something unusual and unstable, the ABC’s Jacob Greber simply states that Australia could look more like Europe after this election. He adds another graph to the mix –the number of seats that have been determined on first preferences in the last 20 years. In 2022 only 15 seats were won with a Labor or Coalition 50 percent primary vote; outcomes in the other 136 seats depended on preference flows.

There are two obvious consequences of this trend. One is that Antony Green’s final appearance on May 3 will be his busiest ever. The other is that election-night parties will drag on for many hours.

The more substantial consequences are harder to predict, but at this stage the most likely outcome is that neither of the old parties will have a majority. A sketch of the number of possible outcomes would have more branches than a mature Moreton Bay Fig tree: speculation would be folly. Most Europeans would be familiar with this pre-election uncertainty.

There is no one pattern of European democracies. Greber seems to be ruling out Britain’s first-past-the-post system, which tends to produce majority governments. Some countries, such as the Nordic countries, tend to have centrist coalitions. By contrast in some countries a coalition forms around a gathering of “right” or “left” gatherings: the Netherlands for example currently has a coalition of right parties.

One gets the impression that European coalition governments are unstable, but that’s because of a few standout examples such as Italy. (Not that we do too well with 8 different prime ministers in 20 years.)

Greber refers to the textbook theory that multi-party coalitions find it hard to implement substantial changes. He points out, however, that our single-party governments of recent years have been hesitant to implement structural reform. When one side of a Westminster two-party system chooses to run scare campaigns rather than to propose alternative policies, paralysis ensues.

In multi-party democracies inaction isn’t an inevitable outcome. Germany’s new Christian Democrat-Social Democrat coalition has come to agreement on fundamental changes in the country’s fiscal and defence policies. (To get some idea of Germany’s government, imagine a Liberal-Labor government, with the Greens, One Nation and the National Party sharing the opposition benches.)

Closer to home our minority Labor government, in office from 2010 to 2013, managed to implement a strong policy on climate change – unmatched by any preceding or following government.

That brings us to the current situation. While Labor and the Coalition are trying to get through an election campaign without confronting difficult issues, the calls for reform and structural change are coming from independents.

1. This graph is constructed from two sources: Parliament Infosheet 22 – Political Parties in the House Of Representatives and Parliamentary Education Office House of Representatives current numbers. ↩

Meet the independents

The 35 on Climate 200’s list

Climate 200 has a website with links to 35 people standing as community independents. Of these 8 are sitting members – Kate Chaney, Zoe Daniel, Helen Haines, Monique Ryan, Sophie Scamps, Rebekha Sharkie (registered as “Centre Alliance” and therefore listed as a party member), Allegra Spender, and Andrew Wilkie.

Of the 35, 28 are women. But what stands out among them is their breadth of experience in the communities they represent. You won’t find a resumé following the template “I have a BA, mastering in politics at the University of XXXX, where I was elected president of the Liberal/Labor club. On graduation I went on to work in the office of Senator/Member XXXX.”

Notably 6 of the candidates are contesting seats in Queensland – a state they seem to have overlooked in 2022. One of these is Ellie Smith. She is standing in Dickson, which Peter Dutton held in 2022 with a 1.7 percent margin.

The unifying issues for all candidates are climate change and administrative integrity – although the emphasis they place on climate change tends to vary, depending on the location of their electorate. They generally want to see the transition to renewable energy kept up or accelerated.

Housing, cost-of-living, and health services are common themes, generally with an emphasis on equity issues associated with these policies. They all mention their specific electorate issues. Some take up gambling reform – an issue ducked by both of the old parties. There is comparatively less mention of foreign policy and defence.

Among the more fully-developed policy proposals is Allegra Spender’s call for tax reform.

David Pocock

Everyone on the Climate 200 list is standing for the House of Representatives. ACT Senator David Pocock is giving community independents a great deal of support. His hold on his seat is strong, particularly in light of the Coalition’s policies on the public service. As a Senator he has more freedom than members of the House of Representatives to state policy preferences.

He is not confronted with that annoying question “which side will you support in a hung Parliament?” In an interview with Karen Barlow of the Saturday Paper he has spelled out what he would demand of a minority government, including a resource rent tax, housing tax reform (including negative gearing and capital gains tax), and of course integrity in government.

Others

Besides the 8 on Climate 200’s list, there are 5 other sitting independents re-contesting their seats.

Zali Steggall is perhaps the best-known community independent, having risen to prominence when she won Warringah off Tony Abbott in 2019. She is not on the Climate 200 list, but this does not imply any falling out. Her successes pre-date Climate 200.

Dai Le won the western Sydney electorate of Fowler, a seat Labor had taken for granted. She seems to be in a strong position to hold her seat.

The other three – Russell Broadbent (Monash), Ian Goodenough (Moore), and Andrew Gee (Calare) were elected as Coalition members (Broadbent and Goodenough were Liberal Party members, Gee was a National Party member) and are running this time as independents. Broadbent and Goodenough both resigned from the Liberal party after losing pre-selection. As one with centrist political views Broadbent became increasing isolated as the party headed to the far right, and Gee resigned in principle when Dutton took a hard line against the Voice. All three seats are being contested by candidates on the Climate 200 list of 35: Deb Leonard – Monash, Nathan Brown – Moore, Kate Hook – Calare.

For the sake of completeness, mention should be made of Bob Katter. Strictly he is not an independent, because he stands as a member of Katter’s Australia Party, and has almost always aligned himself with the Coalition.

Political commentary

Writing in The Conversation Joshua Black of ANU describes the political landscape as seen by the independents: Australia’s embrace of independent political candidates shows there’s no such thing as a safe seat. Black describes the hurdles placed in the way of independents, particularly those who do not have the benefit of incumbency. He also explains the political tactics employed by the Coalition to unseat independents.

ABC journalist Claire Simmonds has a post describing how independents campaign without a party machine behind them. It’s hard work, but they manage to get large crowds turning up to their gatherings.

Brett Worthington has a post Can the teals repeat the success of 2022 at the upcoming election?, giving a history of the independents and speculating on their prospects in this election, including some of the new contenders. He stresses that the independents on Climate 200’s list really are independents: there are many issues on which they do not agree with one another. In this regard he suggests that Climate 200’s main objective is to “deliver more Liberal losses”. Climate 200 would probably disagree with that: their main concern seems to be with the Coalition’s present climate change and energy policies, and with integrity in government. Also not all seats the 35 candidates are contesting are held by the Coalition.

Dirty tactics against independents

If you walk past a newsstand carrying Murdoch newspapers you are more likely to see a headline attacking an independent than one attacking a Labor Party candidate. It’s as if Labor is the established enemy, but there is a special loathing of independents. It’s the feeling most groups have towards traitors. That’s because many independents, particularly the “teals”, come from the Liberal Party’s heartland and have taken once-loyal Liberal voters with them.

Jason Koutsoukis, writing in The Saturday Paper, describes The Murdoch’s attack on the teals, with accounts of the tactics employed in four contests – Wannon, Cowper, Flinders and Mackellar. He describes the reactions of a group who have been attacked from a direction they were not looking. In Wannon for example the Liberals’ Dan Tehan has long rested on the assumption that the community goes along with his idea that politics is about keeping Labor out of office, without having to offer policies of substance from his own party. Alex Dyson has challenged Tehan’s comfortable Weltanschauung.

One of the dirty tactics the Liberals use is to refer to Parliamentary voting records as a basis to assert that “teal” members of Parliament predominately vote with the Greens, implying guilt by association. Bill Browne of the Australia Institute has a post – Who votes with whom? Beware claims that use voting records to argue politicians have similar views – describing how such data is used mischievously.

The ABC’s Matt Martino describes a particularly dirty tactic directed against Allegra Spender. In her Wentworth electorate, which includes a concentration of Jewish people around Bondi, 47 000 leaflets attacking Spenderfor being ”weak” on anti-Semitism have been distributed. The author of the pamphlet is not disclosed, which means there has been a breach of electoral law.

The Electoral Commission is investigating the incident. The ABC has managed to track down the company that printed the leaflets – a company that has done work for the Liberal Party in the past.

A guide to minority government

A most probable scenario is that on Sunday May 4, after the drama of election night, politically-concerned Australians will be wandering around asking wtf happens now. That’s if the previous evening finishes up with no party winning the 76 seats necessary to form a majority government. At this stage the Coalition’s chances of that are about as good as Trump’s bid for the Nobel Prize. Labor’s prospects are better, but the smart money is still on a minority Labor government.

But how might that happen? If Labor is a few seats short of a majority does it simply negotiate a deal with whomever has the numbers on the so-called “crossbench” to ensure supply and to refrain from moving a no-confidence motion?

That’s one possible outcome, but it would be the worst, argues Bob Brown in a Saturday Paper contribution A guide to minority government.

Bob Brown has experience. In 1989 he led the Greens in formulating a Labor-Green accord after the 1989 Tasmanian state election, and in 2010 he helped the Greens broker a deal that allowed the Gillard government to steer through Parliament a raft of legislation to do with climate change and reforms that improved the parliamentary voice of the crossbench. He also mentions the success the Greens have had in the ACT, which has rarely had a majority government.

Even those who might not fully endorse the Greens’ agenda should consider Brown’s tactical advice. If, after election of a minority government, the crossbench isn’t going to be rendered powerless and face elimination at the next election, it should use its power to at least negotiate a formal agreement with specified conditions on important issues, particularly climate change and housing. He argues that such an agreement has to be negotiated at the outset:

If neither old party wins a majority, the weeks after an election are the crossbenchers’ most powerful time in the whole period of government in terms of gaining policy outcomes. Never underestimate the eagerness of Labor and the Coalition to negotiate their way back to the Treasury benches.

Andrew Wilkie, an independent with many years’ experience, does not see much value in such agreements, however. He explains on Casey Briggs’ program Swingers: how to win an election, that he had what appeared to be a binding agreement with the Gillard government on gambling reform, that she broke with impunity.