Economics

IMF outlook: Trump’s trail of destruction

The IMF World Economic Outlook for April revises downward its forecasts for world growth. Global growth is projected to be 2.8 percent this year, down from 3.3 percent in the IMF’s January forecast, and 3.0 percent in 2026, down from 3.3 percent. The sharpest drop this year will be in the US – 1.8 percent, down from 2.7 percent. But it could be worse for the US where people are talking about the strong possibility of a recession.

Although its summary is in bland terms (it doesn’t want Trump’s goons raiding its Washington offices), in the body of the outlook it identifies the source of the shock that has rocked the world economy:

… major policy shifts are resetting the global trade system and giving rise to uncertainty that is once again testing the resilience of the global economy. Since February, the United States has announced multiple waves of tariffs against trading partners, some of which have invoked countermeasures. Markets first took the announcements mostly in stride, until the United States’ near-universal application of tariffs on April 2, which triggered historic drops in major equity indices and spikes in bond yields, followed by a partial recovery after the pause and additional carve-outs announced on and after April 9.

Australia’s growth this year is expected to be 1.6 percent, down from the IMF’s 2.1 percent projection in January. Next year our growth should be 2.1 percent, down from 2.2 percent in the January projection. It projects that our inflation this year will be 2.5 percent, rising to 3.5 percent next year, while our unemployment rate will rise from 4.3 percent to 4.5 percent.

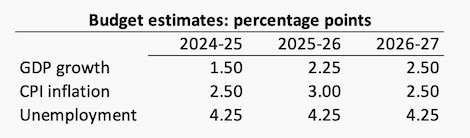

Because the IMF data is on a calendar-year basis and ours is on a financial-year basis, direct comparison is difficult, but the IMF’s figures are somewhat negative compared with the figures presented in our budget last month, before the full onslaught of the Trump madness.

That’s the IMF’s view on April 23. Their projections next week could be different, depending on Trump’s whims. But that uncertainty itself is the source of most of the trouble.

The Outlook also covers two long-term developments – ageing, and policies on migration and refugees. On ageing it stresses the need for policies that support healthy ageing and that close gender gaps. On migration the IMF supports policies that facilitate, rather than hinder, immigration. Boosting infrastructure investment and encouraging private sector investment should ensure countries get the maximum benefits from taking in immigrants.

With policies that direct resources to the care economy, that are open to immigration, and that encourage private investment contributing to our energy transformation, our government’s policies appear to be on the right track to get a tick from the IMF.

Dutton has a good idea but it’s only an “aspiration”

A long time can pass between economically sensible propositions emerging from the Coalition’s ranks: John Howard’s GST was introduced more than a quarter of a century ago.

Peter Dutton, however, may have broken the drought with his idea – an “aspiration” rather than an election promise – to index income tax brackets to inflation, thus eliminating what is known as “bracket creep”. That is the way increases in your nominal income result in your paying more tax, not just in nominal terms, but also in real terms.

Typically over a three-year election cycle, for the first two years bracket creep increases the amount of tax governments collect, and in the third year they hand most of it back in a tax cut. It’s a politically neat way to stave off calls for tax reform.

Economists like the idea of tax bracket indexation, because it would break this pattern, forcing more fiscal discipline on governments.

To get some idea of how tax bracket indexation would work I constructed a simple spreadsheet model, which allows you to plug in different assumptions of inflation, because the higher the inflation rate, the more strongly does bracket creep work to collect more tax.

The model simulates the effect of your getting a boost in income, equal to inflation, if, as at present, there is no change in tax scales. In other words it calculates the cost to taxpayers of not having bracket indexation.

For example, if your income is $80 000, inflation is 2.5 percent (the middle of the RBA’s range), and your nominal income therefore rises by 2.5 percent to $82 000, the amount of income tax you pay would rise from $16 024 to $16 664, an increase of $640 or 0.80 percent of gross income, or a 1.0 percent difference in your income after tax.

For all incomes between about $45 000 and $200 000, the lack of bracket indexation results in taxpayers paying between around 0.8 to 1.2 percent – say 1.0 percent – more tax each year, when inflation is around 2.5 percent. There’s not much for those on lower incomes.

Accumulated over three years, the amount of extra tax one pays because brackets are not indexed mounts up. For our taxpayer on $80 000 that extra tax would accumulate to $1 280 after two years and $1 920 after three years, making way for the government or the opposition to offer a significant tax cut in the election year.

The political appeal of not indexing tax brackets is obvious. By contrast indexing brackets doesn’t have much going for it politically. Imagine our taxpayer on an income of $80 000, paid fortnightly. On the first payday after July 1 she gets a $25 rise compensating for inflation. It will probably pass unnoticed. And even if she does notice it, it is unlikely to coincide with the timing for an election.

Although economists like the idea of tax bracket indexation, fiscal hawks like the present system, because in times of high inflation it acts as a de-facto stabilizer, reducing disposable income. To illustrate the point, plug in 7.8 percent – the peak annual inflation rate the Albanese government inherited from the Coalition – into the model. That takes just on $2 000 from our $80 000 income earner. No wonder the Albanese government was able to deliver two fiscal surpluses, and tax cuts, in a poorly-performing economy suffering from decades of structural neglect.

We probably won’t hear much more of Dutton’s “aspiration”. It’s hard to explain bracket creep to an electorate that has been fed so much bullshit and misinformation about tax and fiscal matters over the years. And if anyone in the Coalition did try to explain it, they would be drawn into talking about the relationship between tax and inflation, which means exposing the way our capital gains tax system, as modified by John Howard, has been so distortionary and unfair.

While I was modelling Dutton’s tax “aspiration” I also modelled the government’s lowering of the first income tax bracket from 16 to 14 percent. This is in the second spreadsheet. It’s not a big reform but it’s mildly progressive.

Confirmation – the Albanese government really is a Labor government

A group of researchers at ANU’s Centre for Social Policy Research have analysed the Albanese government’s tax and welfare changes over the last three years, and have concluded that they have been of most benefit to those in the middle and lower bands of living standards: Analysis of 2025 budget and Albanese government tax and welfare changes.

The analysis covers the government’s budgets, the modified “Stage 3 tax cuts”, and other changes with direct effects on disposable incomes, including Jobseeker, parenting payment, rent assistance and child care subsidies.

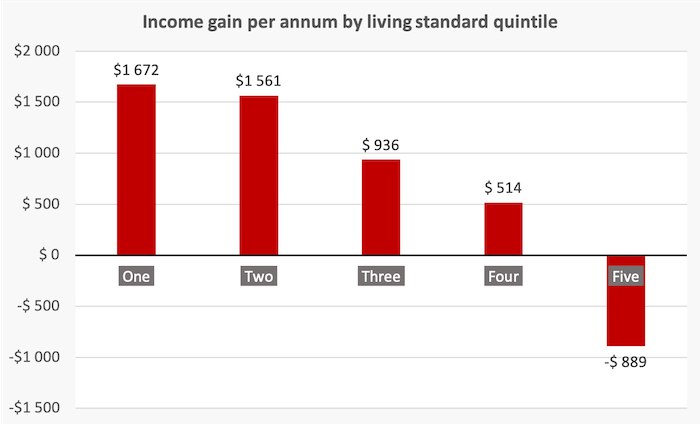

It finds that the gains have been spread across quintiles 1 to 4 of the income distribution spectrum, with a concentration of benefits in the third (middle) quintile. Those in the top quintile have been net payers.

A stronger indication of redistribution is revealed when the gains and losses are analysed by “living standard” quintiles, a measure that takes into consideration wealth as well as income. This distribution is shown in the chart below, essentially a copy of the researchers’ chart.

The paper includes maps of the distribution of the benefits in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane, indicating clearly that the beneficiaries have been those living in outer suburbs, traditional Labor territory now contested by the Coalition, while the losers have been those in prosperous inner suburbs. It also shows that outback areas of New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory have done well from the Albanese government’s distributional policies.

Notably the ANU researchers did not include changes in health and education policies, which also have distributional effects. Nor did they include the benefits of progress towards closing the gender pay gap, which apply particularly to low-paid workers in the care economy. Fiona Macdonald of RMIT University describes this progress in a Conversation post: A landmark ruling will tackle the gender pay gap for thousands of workers.

One may wonder why Labor hasn’t mentioned this ANU research in its campaign. It could provide an opportunity for Labor to reassure voters that it has stuck to traditional Labor principles and has not neglected the outer suburbs. But in an election where evidence of re-distribution can be overridden by the Trump-Dutton question “Are you as well off as you were when Labor was elected?” the message may be hard to sell.

The researchers find that most of the redistributional benefits result from the re-jigged “Stage 3” tax cuts. In all they find that “the general nature of reform in personal income tax and welfare has been one of renovation rather than major reform during the Albanese tenure”. Although it is not included in their analysis, the researchers conclude that the government’s initiative to cut the lowest marginal tax rate from 16 percent to 14 percent will not help the very poorest, because the first bracket cuts in only at an income of $18 200. (The effect is modelled in a linked Excel file.)

Writing in The Conversation – Post-election tax reform is the key to reversing Australia’s growing wealth divide– Helen Hodgson of Curtin University argues that changing income tax scales doesn’t count as “reform”. Joining a number of economists, and some independent members of Parliament calling for tax reform, she wants the government to implement a wide-ranging tax reform agenda which would include (but not be limited to) a review of concessions relating to superannuation, capital gains and negative gearing.