Economics

Our credit rating and election costings

Ratings agency S&P has warned that our AAA sovereign credit rating could be at risk if election spending promises result in larger structural deficits, debt and interest costs.

S&P keeps its data behind a strong paywall: they even restrict their press releases. Yahoo Finance has a short summary, and Alan Kohler has a short podcast.

Labor’s costings

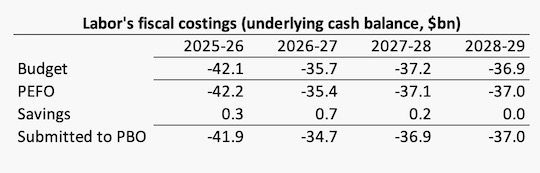

Labor has submitted its costings to the Parliamentary Budget Office. It has published its costings which are in a detailed statement. These are summarized below.

Within a small band the underlying cash deficits in Labor’s costings are almost the same as those in the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook, which are almost the same as in the March budget. The arithmetical magic of hardly-changed figures is shown below.

How do they achieve this while making so many election promises? In part it’s about building some slack into the budget in the first place, and in any case the budget already had most major recurrent spending costed. In these costings they have added savings of $6.4 billion in reducing the use of consultants and contractors – a point in the context of the Coalition’s promise to reduce the public service by 41 000.

There is no change in these deficits as a percentage of GDP: they’re all within 1.0 to 1.5 percent of GDP, in line with other countries that are operating conservative fiscal policies.

Albanese insists that Australia’s AAA credit rating, a rating it shares with only 9 other countries (Canada, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland) is not at risk.

S&P is particularly concerned about off-budget spending, which includes allocations to and withdrawals from future funds, such as Rewiring Australia, the NBN, Snowy Hydro, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Housing Australia Future Fund. The budget estimates that the net cash flow associated with investment in such financial assets will be between $19 and $23 billion a year between now and 2028-29.

Labor has been critical of the Coalition for its delay in submitting its election costings. On Radio National Finance Minister Katy Gallagher explains Labor’s fiscal figures – where it plans to spend financed by offsetting cuts. She explains that the biggest threat to the budget is the Coalition’s $600 billion for nuclear power stations: Labor demand Coalition release costing of its election. (9 minutes)

The Coalition’s costings

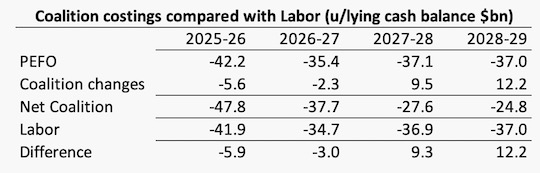

The Coalition produced its plans late on Thursday. Its costings, compared with Labor’s, are shown in the table below.

Its higher deficit in the first year is mainly due to the $7.4 billion cost of reducing fuel excise, and in the second year is mainly due to its so-called “cost of living tax offset”, costing $9.1 billion in that year. The savings from cutting the public service are in its costings – $17.3 billion over 4 years.

Labor has been pointing out that the Coalition’s nuclear plan would make huge demands on the government’s cash flow (pick a big number rounded to the nearest trillion). But all we see in the Coalition’s 4-year costings are small outlays for the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency, the Nuclear Energy Coordinating Authority, and the National Nuclear Training Facility and fuel laboratory. It mentions longer-term outlays in an explanation, with ridiculously low estimates:

To deliver our [nuclear] plan, the Coalition will provide $36.4 billion in equity investments through to 2035, rising to a total of $118.2 billion through to 2050.

If the Coalition were to be honest these outlays would never be made, because its plan almost certainly to continue using fossil fuel to generate electricity.

The ABC’s Tom Crowley has a summary of the Coalition’s costings: Coalition election promise costings reveal worse budget bottom line for two years compared to Labor's.

Noting that the Coalition’s deficit for the for the first two years is higher than Labor’s the media has generally said it’s a “worse” deficit than Labor’s. This will not help the Coalition electorally. But in view of the possibility that Australia will be exposed to a global downturn, a mildly expansive fiscal policy is probably sound economic management. For once the a Coalition policy makes economic sense, but they’re cettng condemned for it.

There is poetic justice in this adverse judgement, because for as long as one can remember, the Coalition has preached to the electorate that fiscal surpluses are “good”, that fiscal deficits are “bad”, and that the economic competece of governments should be judged on these measures.

Too much finance, too little economics

It’s hard to take the whole process too seriously. Steve Bartos of the University of Canberra has a Conversation contribution – How much do election promises cost? And why have we had to wait so long to see the costings? – explaining the limits of the pre-election costing process. By the time Labor had released its plans perhaps 15 percent of Australians had voted, and we probably won’t be seeing the PBO’s analysis until the middle of the year.

As Bartos points out, unless we spend time in the last couple of days poring over numbers, we vote without knowing the parties’ fiscal proposals, proposals that have implications for future taxes, interest rates, and the government’s ability to fund new and ongoing programs.

Knowing the parties’ contending fiscal plans would be a benefit, but fiscal management is only one small aspect of government economic management. Even more basically we go to the ballot box without any independent assessment of parties’ economic plans – policies on income distribution, housing, education, health care, infrastructure …

CPI inflation

On Wednesday the ABS released the Consumer Price Index for the March quarter. It also released the Monthly CPI Indicator for March.

Based on the March quarter figures, CPI inflation has been 2.4 percent over the last 12 months. Trimmed mean CPI inflation, the RBA’s preferred indicator, is 2.9 percent. Both fall within the RBA’s comfort zone of two to three percent. Most commentators expect the RBA to drop interest rates, by a modest 25 basis points when it makes its next announcement on Tuesday May 20.

Had there been an increase in either of these CPI numbers the opposition would have come out with all its remaining guns blaring, blaming Labor’s reckless spending for boosting inflation, but the indicators are politically neutral.

Gareth Hutchens has a post Headline inflation stable at 2.4pc while RBA's preferred measure drops within target, with some extra detail on electricity prices, particularly as they are affected by government rebates.

Electricity prices have fallen

Within these numbers it’s informative to look at electricity prices before rebates. They had a big jump between the June and September quarters in 2023. But over the following 18 months to March this year they have fallen by 2.1 percent.

That is a significant real fall of about 6 percent, because the CPI over all goods and services over the same period has risen by about 6 percent. But the government does not dare to make this point, because journalists, hungry for gotchas, would inevitably come back to that original $275 promise, made more than three years ago.

The Trumpian gold rush

A reader has drawn attention to an article in Livewire Markets Why Aussies are queueing up at Martin Place to buy physical gold as prices surge.

It explains the usual theory of finance that as interest rates fall people seek other investments. But when share prices are volatile, and there is an atmosphere of uncertainty, there is a rush to gold. Gold prices sometimes track the US government bond market, both having been regarded as safe havens: low $US bond yields have generally correlated with high gold prices. But trust in US-denominated assets, including bonds, has fallen, which is why there has been such strong demand for gold.

The sudden loss in faith in the $US was described in the roundup of 19 April – “Trashing the Greenback”.

The reference to queuing up for gold is not just a metaphor. Many people are buying the metal, including 37.5 gram gold Taels, worn as jewellery.

The author of the article, Tom Richardson, explains how if 20 years ago you had invested in gold rather than shares, you would have done rather well. His explanation is unorthodox and difficult to follow, and it does not account for movements in the $A/$US. Working on his data and adjusting for exchange rate movements, the real annual return on shares (the S&P/ASX Accumulation Index) has been about 5.1 percent, while the real return on gold, expressed as an annual growth in value, has been 9.1 percent.

Risk free? Not really. An outbreak of good government in the US could send gold tumbling.

Unemployment

One closely-watched series is the unemployment rate, reported in the ABS monthly Labour Force releases. This is the figure, currently 4.0 percent, that tripped up Albanese in a gotcha question in the 2022 election campaign.

Our labour market is a great deal more complex than can be indicated by a single number and the ABS provides a great deal more than this single piece of information.

To help people understand unemployment, the Reserve Bank has produced a neat explanation of Unemployment: its measurement and types. It’s essentially a year 12/first year university text, explaining not only how agencies like the ABS measure unemployment, but also the common classifications of unemployment – cyclical, structural and frictional.

Immigration

Wrong metaphor

It is hard for the public to understand how immigration works. We carry around a mental model of a tap as a metaphor. Open the tap to bring in more migrants, turn it down to reduce the flow.

Opportunistic politicians like Dutton exploit this mental model to spin a story that the irresponsible Labor government has let in far too many migrants, pushing up demand for housing and contributing to stresses on public services.

But it’s a lousy metaphor.

Immigration is complex. There is a migration program, over which the government has some control, and there is a balance of flows into and out of the country, over which the government has almost no control.

And politically within the Coalition there is pressure to sustain immigration: the National Party wants to see a flow of “backpackers” to work on farms and foreign students to sustain the viability of universities in non-metropolitan regions.

Peter McDonald of the University of Melbourne has a Conversation contribution – Cutting migrant numbers won’t help housing – the real immigration problems not being tackled this election – explaining the ways governments can and cannot regulate migration flows, and providing some numbers around those flows, demonstrating that our government has only limited flexibility in the short to medium term.

Laura Tingle has a 9-minute video (an extract from the 730 program), including interviews with immigration experts (Peter Mares, Abul Rizvi, Alan Gamlen, Aruna Sathanapally) explaining how immigration works in Australia – the mechanisms and the politics – and the numbers over the recent years. The Covid pandemic caused a large disruption, providing plenty of figures for Dutton to make out-of-context claims about Labor being out of control, but the numbers are actually back on a long-term trend.

Over recent years, however, there has been a change in the composition of migration, with the balance tilting towards more short-term migration. That shift has taken place with little public deliberation.

Related to immigration, the ABS has just released a publication of Australia’s population by country of birth. From 1891 to 1947 the proportion of our population born overseas fell from 32 percent to 10 percent, but it is now up to 32 percent. England still holds top place, but at present rates India should soon overtake it and China should do so a little later.

It is notable that among overseas-born immigrants, those born in India and Nepal have sex ratios (male:female) above 110:100, while the sex ratios for most east Asian countries are 90:100 or lower.

Can the Commonwealth budget for natural disasters?

The Commonwealth is often hit with the need to spend on disaster recovery, but it doesn’t include such expenditure in its budgets.

A Centre for Policy Development paper by Toby Phillips, Warwick Smith and Guy Debelle – Budgeting for natural disasters – points out that on average the Commonwealth spends $1.6 billion on disaster recovery, but budgets for only $215 million.

The Commonwealth justifies this practice on the basis that while it can budget for normal contingencies, such as those relating to unexpected demands on social security benefits, it does not budget anything for natural disasters, basically because it cannot produce an estimate approaching accurate forecasts for such outlays.

The authors demonstrate, however, that while the amounts to be spent are indeed unpredictable, it is close to certain that they will be incurred. As evidence they show the gaps, going back to 2012, between expenditure and forward estimate outlays.

The authors put forward their preferred principle for natural disaster budgeting:

… the expected cost of future natural disasters should show up in the fiscal aggregates rather than be treated as an unquantified contingent liability. Merely disclosing these costs in a qualitative risk statement without formally recognising them as expenditure falls short of transparent and responsible budgeting. Moreover, this natural disaster expenditure is effectively locked in. It is not discretionary and hence should be budgeted for like other non-discretionary spending.

The issue is about the treatment of risk and uncertainty.

Budgeting for risk is about budgeting for costs that can be estimated using reasonably accurate statistical models, where events are often distributed around a Gaussian normal distribution curve or something closely approaching one. For example, insurance companies can insure people's cars because the number and cost of accidents is reasonably predictable, within a tight distribution of outcomes.

Uncertainty, however, does not lend itself to statistical modelling, and does not fit with accountants' preference for precision wherever possible.

The merit of the authors' recommendation to budget for significant contingencies is that it would bring the cost of natural disasters to the attention of policymakers, possibly making governments more amenable to invest in mitigation. It should also make it easier for fast approval and funding of repairs to infrastructure.

There is one catch, and it’s political. Imagine if the government, already under unreasonable pressure to produce balanced budgets, were to add another $1.6 billion a year to budgeted outlays. It would result in more hysterical claims by the opposition that “Labor can’t manage money”, and that “Labor’s reckless spending will drive runaway inflation”. A precondition for the authors’ sensible recommendations is a mature understanding of fiscal management among the public.