The election’s outcomes and consequences

The numbers

To put it simply, the Coalition primary vote is down by about 4 percent, and the gain in support has been shared equally by independents and Labor. Labor now has at least 90 seats in the 150-member House of Representatives and enough seats in the Senate to give it an easier run in passing legislation.

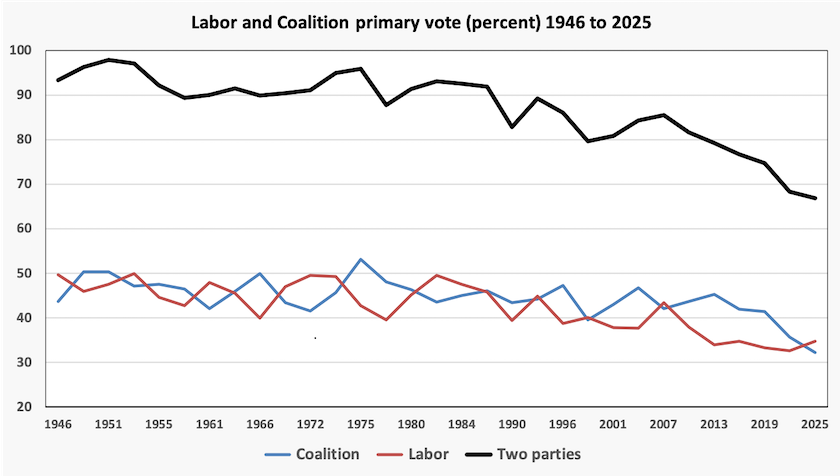

There was a swing to Labor, but the trend away from the two-party duopoly is unbroken

The combined Coalition plus Labor primary vote has been on a downward path for 50 years. In this election a 2.2 percent swing towards Labor was more than offset by a 3.5 percent swing against the Coalition. In the three federal elections since 2013 the Coalition’s vote has fallen even faster than the long-term trend against the two old parties.

It is not only in federal elections that the Coalition vote has retreated. In 24 out of 28 state, territory and federal elections over the ten years since late 2014, the Coalition’s primary vote has gone backwards.

The Greens too lost support in this election, suffering a loss of 0.5 percent. This means that between them the Greens and the Coalition have lost 4.0 percent, only 2.2 percentage points of which has gone to Labor.

It’s hard to trace that other 1.8 percent. It will be some time before political analysis give us firm data, but the evidence suggests that while a little may have gone to parties on the far right, the main beneficiaries are independents, although that does not show up in increased representation.

Not picked up in thsese numbers is the way political parties have lost control. Hardly any seats, or perhaps no seats, have been won on first preserences. Local candidates, whatever their party or non-party affiliation, have to be more responsive to their communities. Central office endorsement counts for less than it once did, and similarly central office directions to follow policy lines can act against candidates’ chances.

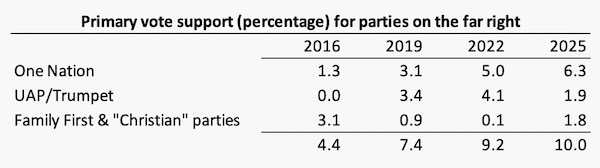

The far right might have picked up one percent

Movements in support for parties on the far right are shown below. This goes back to 2016, the year of Brexit and Trump’s first election win. It appears that over this period Australia has not been immune to the worldwide swing to the far right, but it has not carried through to this election.

If one counts only One Nation and Clive Palmer’s parties as “far right”, their combined vote has gone backwards – from 9.1 percent to 8.2 percent.

If one classifies Family First and parties who have used the word “Christian” in their names as far right, the total figures suggest that there has been a small improvement in support for the far right.

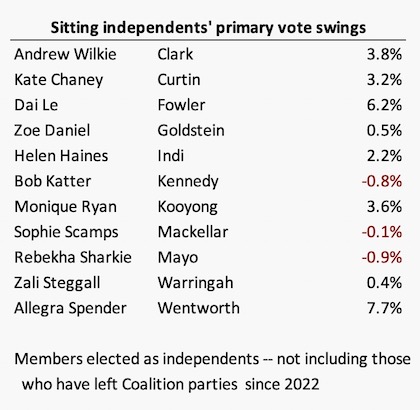

Support for independents has improved

The ABC reports that support for “others” (excluding Labor, Coalition, Greens, One Nation and the Trumpet) has risen by 2.8 percent.

One story doing the rounds is that support for independents has fallen or plateaued. Maybe that’s because Zoe Daniel has lost her seat of Goldstein, and Monique Ryan is only just holding on to her seat in Kooyong. But 8 of the 11 independents in the House of Representatives seeking re-election saw a rise in their primary vote, and the other 3 hardly lost support.

Besides these improved primary votes for sitting members, a number of well-organized independents, including those supported by Climate 200, have made impressive inroads in seats such as Bradfield (likely to stay with Liberal), and Fremantle (narrowly won by Labor). In the Calare electorate Andrew Gee, having left the National party over its stance in the Voice referendum, has held on to his seat.

These figures are as at Thursday and they don’t take into account boundary changes, but they are certainly not consistent with the idea that independents have lost support.

Support for the Greens has slipped

Between 2016 and 2022 the Greens’ primary vote rose from 10.3 percent to 12.3 percent. In this election it has fallen to 11.7 percent. Their representation in the House has fallen from 4 seats to 1, assuming they hold on to Ryan in Brisbane.

Polling over the last three years showed a rise in Green support over 2022 and 2023, reaching as high as 15 percent, before it slowly tapered off. That same research showed that while Green support has held up among young voters, older Green voters, annoyed by the Greens’ alliances with the Coalition, reverted to Labor.

Outcomes – Labor domination in the House of Representatives, an easier Senate

Based on counting figures available on Friday, including probable outcomes in 10 seats still undecided, in the House of Repesentatives Labor will have 93 seats, the Coalition 44, independents 12, and the Greens 1.

The breakdown is shown below

The Senate count is less advanced, but it shows an improved outcome for Labor. In my last roundup I was among many who predicted that the Senate would see little change, but I was wrong. Labor has surprised itself by probably picking up the third Senate seat in New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia, and a second seat in Queensland.

The probable Senate outcome therefore is Labor 28, Coalition 26, Greens 11, others 11. If one assumes a simple “left-right” frame, this means it would be easy for the government to secure 39 votes (Labor plus Green) supporting “left” legislation: that’s just enough in the 76-seat chamber. The reality is likely to be messier.

Most media commentators say that with its huge majority in the House of Representatives, Labor is set up for two terms of government. They may be overlooking the fluidity of the electorate. Research shows a strong trend away from party loyalty. Party loyalty is largely confined to a cohort of older voters who are being replaced by others who are less attached to any party. It should be remembered that in this election 65 percent of voters did not give their primary vote to Labor.

And we should never overlook Labor’s exquisite capacity to turn a political victory into an opportunity for self-destruction. It is off to a start with the probable dumping of two competent and experienced ministers, in order to make space for factional fighters.

But we can say with some more certainty that whoever tries to dislodge the government at the next election (maybe the Coalition, but three years gives plenty of time to construct a new party), would have to do very well in the next half-Senate election in view of the strong continuing position of Labor and the Greens.

The new regional divide

Two thirds of Australians live in our eight state and territory capitals. These are now pretty well Labor territory.

Of the Liberals’ probable 19 seats, only 7 are classified as metropolitan (“inner metropolitan” or “outer metropolitan”) by Electoral Commission definitions. They hold 4 metropolitan seats in Sydney (Lindsay, Berowra, Mitchell, Cook), two in Melbourne (Goldstein, Latrobe), one in Perth (Canning), and none in the other 5 capitals.

To these could be added two Brisbane seats (Bowman and Fadden) held by the LNP.

For the Coalition that comes to 9 capital city seats in a chamber of 150. That’s 81 seats short of what a spread of representation would look like if it were matched to the population distribution.

Some Coalition optimists might point out that they still hold some large urban centres such as the Gold Coast, but it’s in the capital cities where the businesses have their head offices, where state and Commonwealth governments have their offices, where there are long-established universities and research institutes, and where immigrants settle.

Our rural regions are different. The further we live from a capital city the more likely we are to be poor and unhealthy, and the less likely we are to have a sound education or to be descended from recent immigrants. Our non-metropolitan regions are those most badly affected by climate change, but they are also the regions where live those who are most hostile to action to deal with climate change – a hostility inflamed by Coalition politicians.

We can see that division in other countries, most starkly in the US, where Trump and his followers refer to the division between the “elites” and others. That division now maps better than ever before along party lines.

The Coalition’s divide

Within the Coalition parties the swings were far from even. The Liberal Party lost 3.0 percent while the National Party gained 0.4 percent. This is already making for some blame-shifting within the Coalition.

But it gets more complex, because the LNP lost support, their vote going backwards by 0.9 percent. Is the LNP simply the Queensland branch of the National Party?

When it comes to party numbers, within the Coalition’s 44 seats, the Liberal Party will hold only 19 seats, the Liberal-National Party 16, and the National Party 9. Because only 2 of the LNP’s 16 seats are in Brisbane, one could consider that the National Party will have a caucus of up to 23 in the Coalition, a small majority.

So far the two parties (or is that three parties?) are treating this outcome as if it is about “shadow” positions on the front bench. But to any outside observer, unburdened by assumptions about coalition conventions, the situation looks to be highly unstable.

There was a time when the Coalition was dominated by the Liberal Party, whose ideology was on the economic right with an emphasis on free markets. The Liberals accepted the National Party’s (previously Country Party) “bucolic socialism” as a small compromise which could be isolated to the rural sector.

Those days have passed, and the National Party have been pushing policies that go well beyond a few roads and dams. A crazy Commonwealth-owned nuclear power system is the standout example.

He chose the name “Liberal” deliberately

Therefore the chance that the Coalition as it is presently constituted can present a consistent economic policy to the electorate is slim.

Some compare the Coalition’s present situation to that of the United Australia Party in 1944, which resulted in a complete reconstitution of the UAP as the Liberal Party – a name Menzies deliberately chose. If Menzies could be summonsed in a joint party séance he might suggest that the Liberals now go it alone and break their association with the National Party and the LNP.

A more radical approach would be for the Liberal Party to dissolve itself, making way for a gathering of former liberals, independents, and defectors from the National Party and the LNP to form a centrist political party. Radical? Not really, because it’s close to what Menzies did in 1944.

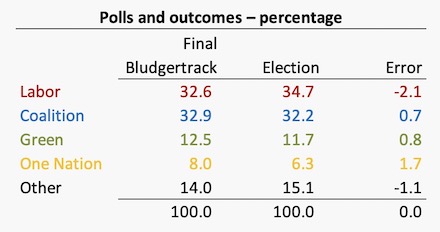

The polls that got it wrong

Most commentators were surprised by the outcome. The differences between the final polls, as collated in William Bowe’s Bludgertrack and the election outcome, are shown below. Labor’s support was badly underestimated.

It’s possible that opinion polls taken during an election campaign have a bias against the government. Some people could see an opinion poll as a chance to lodge a protest against the government – a protest without consequence – but they come back to the government when they turn up to vote.

Among the regular polls there was one, Freshwater, that was almost always showing much higher support for the Coalition than the others. So high was the imbalance that it has a one or two effect on the average most of the time. The ABC’s Tom Crowley has a post Most polls underestimated Labor. How did they get it wrong?.

Crowley also explains another bias that may have affected all polls – the difficulty in polling young people, whose vote was strongly anti-Coalition.

Then there is the general media bias where the story is almost always about a tight contest. They have an incentive to maintain public interest, and media that seek to be politically neutral, the ABC in particular, see safety in downplaying evidence of the public moving in one direction. (Notice the predictable balanced in those street interviews.)

Sources

Numerical nerds who find joy in building spreadsheets and analysing results, or others who want to update these figures, can go to:

The Australian Election Commission Tally Room

ABC Federal Election 2025 – Australia Votes

William Bowe’s Poll Bludger Results Summary

What explains the shift?

We don’t know, but that isn’t for a lack of offerings:

- in uncertain times we have stuck with our elected government;

- after a cut in interest rates and as inflation has abated we are noticing an improvement in our finances;

- we don’t believe the Coalition could have done better;

- we were turned off by the Coalition’s specific policies, including nuclear power;

- based on our experience with previous Coalition governments we believed that a Coalition government would institute a harsh austerity program;

- we felt patronized by the Coalition’s short-term handouts;

- we thought the Coalition was too obsessed with things that have little connection with our wellbeing;

- we reacted against the Coalition’s unconditional support of Israel;

- the Coalition was contemptuous of women’s concerns;

- the Coalition was contemptuous of young people’s concerns;

- we didn’t know what the Coalition stands for;

- we did know what the Coalition stands for and didn’t like it;

- we thought the Coalition had drifted too far to the right;

- we thought the Coalition had abandoned its pro-market principles;

- we feared the Coalition was heading down a Trumpian path;

- we were turned off Peter Dutton;

- and so on …

Individual voters make their choices for a number of reasons. Unless there is some overwhelming distress or annoyance different groups of voters have different reasons for their choices.

That doesn’t stop political commentators in their quest for one all-explaining reason for political shifts. Until bodies such as the ANU’s Centre for Social Research and Methods run the voting results through multifactor analysis, we do well to avoid attributing the swing to one big factor.

But the Coalition feels under pressure to make some quick assessments before Parliament re-convenes. Their main concern for now is the search for a “leader” of the Liberal Party who will take them back to the promised land, but the more thoughtful in their ranks are talking about their need for “soul-searching” (the term must be in their speaking notes).

The Coalition’s explanations

Flag at RG Menzies House – needs replacing

When it suffers defeat the Coalition goes through a predictable pattern. First they blame the campaign organizers. Enough has been said about that this time. Then they are inclined to blame the “leader”, making him or her (almost always “him” in the Liberal Party’s case) the scapegoat for the party’s failure. If policy gets a mention it’s usually in the context that “our policies didn’t get through to voters”, ignoring the strong possibility that the Coalition’s policies were getting through and that people reacted against them.

It appears that the Coalition has been relying on a chain of logic that starts with the axiom that the Coalition are better economic managers than Labor. Because over the last three years people’s living standards have fallen people would blame the Labor government. Therefore voters would turn to the Coalition, the better economic managers.

Maybe the assumption that people are subject to the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy is not too far off the mark: the question “are you as well-off now as you were three years ago?” has traction for many voters. But those same voters had to believe that the Coalition could do better, and the idea that the Coalition are better economic managers doesn’t hold up.

Some Coalition commenters suggest that had it included an economic policy in the campaign it would have done better. That view is understandable: an electorate concerned with economic wellbeing wasn’t interested in the flags displayed behind the prime minister and didn’t understand what the Commonwealth government had to do with crime rates.

But it is a strange view, because it regards economic policy simply as a campaign tactic, rather than as a basic principle of a political party. There was a time when the Coalition, or more specifically the Liberal Party, was able to differentiate itself from Labor. That time is long past, but it seems to be particularly hard for the Coalition to acknowledge that they are hopelessly at sea when it comes to economic policy.

The Coalition’s economic weakness

When pollsters ask Australians which party is better at economic management, the Coalition almost always comes out on top. But it’s increasingly evident that voters associate “economic management” only with fiscal management. The Coalition has been adept at giving the impression that they are better at handling government finances.

There is so much more to economic management than managing the books, however. Over the long term our material welfare is influenced by policies to do with taxation, immigration, education, public investment – indeed almost every aspect of public policy.

When voters tried to work out the Coalition’s economic policies, or even just get a feel for them, they could find nothing consistent. The idea of cutting 41 000 public service jobs was out of Ronald Reagan’s agenda of austerity and contempt for the public sector. That sat alongside a Soviet-style vision for a massive public investment in nuclear power. There were ideas with elements of “dry” competition policy, such as forcing supermarkets to divest. But that was in contrast to a crony-capitalist idea of letting business managers shout themselves to free entertainment. There were elements of economic spite, particularly towards renewable energy. There was a hostility to learning, manifest in the Coalition’s approach to TAFE fees and student debt. And there was an economic spokesperson, the so-called “shadow treasurer”, making up economic theories that had no basis in the economic canon.

But those inconsistencies didn’t matter to the Coalition. They didn’t need an economic framework, because they knew that they were the party of economic competence, having been assured by the Murdoch media and by opinion polls. They often had the benefit of holding office when the economic cycle was expansionary and commodity prices were high, confirming their belief about themselves. Those assurances protected the Coalition from realizing that it is economically clueless.

The rough economic ride many Australians have had over the last four years results from decades of economic neglect. From around 1996 (John Howard’s election) governments have failed to address ongoing need for structural reform and modernization. Without such reform there is little opportunity for a lift in productivity, and without an improvement in productivity there is little scope for a sustainable increase in real wages.

Attention to economic structure is what economic management should be about, but our political environment, shaped largely by the Coalition’s economic laziness when in government and their reliance on fear campaigns when in opposition, has largely stymied serious action on structural reform.

Re-framing the election outcome – a rejection of the Coalition’s politics

Most media are talking about a Labor landslide victory, while others are talking about the Coalition’s devastating loss, or even an existential threat.

Another way to see the outcome is as a rejection of the Coalition’s way of doing politics, particularly at the federal level. A defender of the Coalition’s tactics can say that Labor too uses scare campaigns, but it’s usually the Coalition that starts the scare campaign.

For some years Labor strategists have been guided by the mantra of running “positive” campaigns. It’s sound advice: researchers find that the public are turned off by scare campaigns. The turnoff is not only a visceral disgust; it is also the difficulty in finding grains of truth among all the lies, misrepresentations, bullshit and loose use of numbers.

When the political landscape is dominated by only two parties, scare campaigns are a zero-sum conflict. But when there are more than two parties, scare campaigns can be costly to those who continue using them. To take a commercial analogy, we don’t see Woolworths trashing Coles, or Coles trashing Woolworths, because they know there are other players.

Among those who are seriously concerned about our economic structure there is a concern, verging on despair, about our capacity to address serious economic questions, because it is so easy to kill a reform proposal with a scare campaign.

Reform is usually the work of parties on the “left” or “progressive” side of the spectrum, while those on the “right” or “conservative” side are generally resistant to change. That makes the scare campaign an easy weapon for conservatives – and they have used it.

That’s understandable if not justified. A party in opposition is always at a disadvantage. The government, once established, just has to go on governing, and has the resources of the public service behind it. The opposition, cut off from those resources, and having to make the best of its situation, finds the scare campaign to be a handy weapon.

The Voice referendum presented the perfect opportunity for the Coalition to mount a scare campaign, and Dutton couldn’t resist the temptation to take it. So successful were his tactics of scaring and dividing that he went on using them, reinforced by Trump’s success in using those same tactics.

Peter Dutton – contempt for democratic processes.

In my election-day post I wrote that anyone who consistently and deliberately valorises voters’ ignorance, shows little respect for the truth, and employs the politics of division, is not suited to hold office in a democracy.

To stress the point, that is a comment on the behaviour Dutton exhibited in the political arena. His concession speech exhibited a completely different behaviour, however. It was probably a personal effort rather than one of the prepared speeches – no one on his staff could have anticipated the outcome.

It was a statement by someone who is capable of conducting civilized discourse with grace and respect. It was as if he could suddenly shed his “political” persona and become a normal, concerned and polite Australian citizen.

There must have been many Coalition supporters, watching the election count, who wished he had exhibited that behaviour over the last three years. He could have still campaigned against the Voice, but using rational argument and drawing on evidence, rather than conducting a deceitful and divisive scare campaign, and telling people that they didn’t have to inform themselves before casting a vote.

Many have already said that Dutton’s behaviour during the campaign was politically inept because he was talking to his base rather than to those he should have won over.

But more basically his chosen behaviour, his assumption that in an election campaign norms of civilized discourse do not apply, shows a disrespect for democratic processes. All politicians should learn from Dutton’s downfall.